If it wasn’t obvious already, Greeks do their taxes differently.. They rely more than is customary in OECD on the less visible taxes of VAT and Social Security. Income tax revenue (from people and companies) is much less prominent. If they are risking a lot less, it time to try to actually lower the income tax rate?

In a democratic system, popular ideas about who should pay taxes (people? companies? smokers?) may influence the tax system, but may also themselves be influenced by the system and its “traditions”.

Our recent post illustrated the Greek application of a popular idea that companies should pay as much as possible while people should not debase themselves with such trivialities as taxes. The two case studies are interesting, but just how does the Greek tax system in general differ from the rest of the inudstrialised world?

Who actually pays Greek income taxes, people or corporations?

It is often popular – though somewhat naïve – to use the headline figure of (income) tax rates across countries. This does not actually reveal much, different countries offer different discounts, exemptions, etc. Also, different tax authorities will tolerate different levels of loophole exploitation, and total tax burden also differs greatly across countries. To fairly assess the relative burdens of each type of tax, we consider what share of the total tax revenue (whatever it is) it contributes. In Greece and in the OECD area (on average).

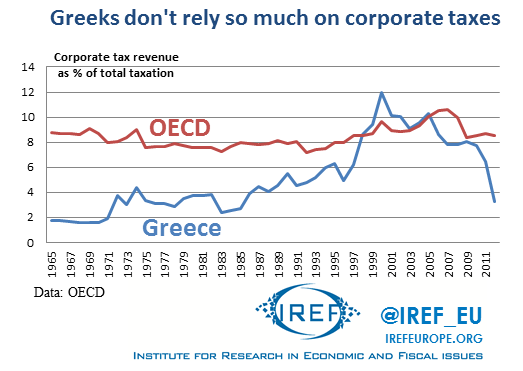

By OECD standards, Greece historically relied very little on corporate tax revenue. Not even access to the EU common market in 1981 had much impact on its role. Only roughly from the 1990s does the share start to rise (and briefly even exceeds) OECD levels, only to decline in the aftermath of 2007 to its “traditionally” low levels as the Greek economy stopped working, choked by high government debt.

So clearly, Greek expectations that companies pay a greater share were rising in recent history. How did it compare to revenue from personal income taxes?

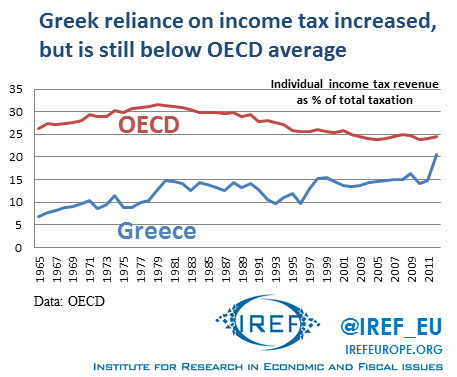

The picture is different. Although personal income tax also contributed much less to the Greek government revenue than is customary, its share was increasing much less dramatically – and almost imperceptibly since late 1970s. Meanwhile, the average OECD share was gradually falling and becoming more “Greek”.

We can therefore conclude that Greek reliance (and expectations?) on corporations has risen much more than reliance on personal income tax for general revenue.

However, these graphs beg another question. If both income tax shares are generally well below OECD standards, just where does the Greek government get its revenue, historically speaking?

So where does Greek government get its revenue?

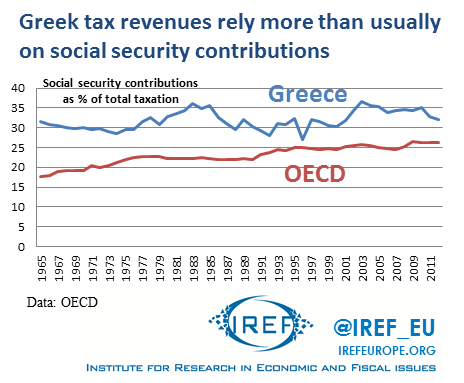

One possibility is to look for a classic “hide-out” within income taxes. Modern governments often try to arbitrarily hide a part of income taxes under the heading “Social Security contributions”. Governments do this because these are less mentioned in international tax rate comparisons and because they are partly levied on corporations, hiding them from the employees (who are still paying them). In spite of all this, social security behaves like an income tax.

Here we seem to have caught at least part of the “missing Greek revenue”. Although the gap is getting smaller over time, Greek government collects consistently more in social security than is the norm in OECD countries. Some may argue that this is purely to finance the famed system of benefits and 14th salaries, but the fact is that in virtually all countries any surpluses of the social security “fund” are treated as general government revenue.

Still, this does not explain all of the missing revenue, and so the search continues.

Greek property tax revenue generally mimics the OECD experience and never accounts for more than 2% of total revenue anyway.

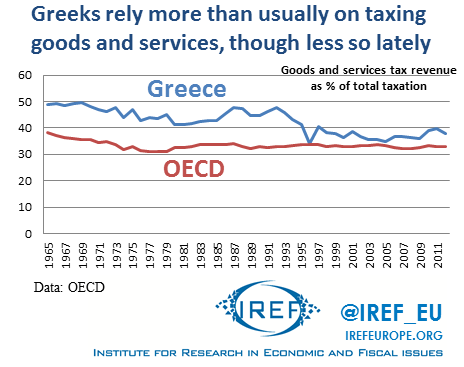

That leaves us with the last resort to look at – taxes on goods and services.

Bingo! Until mid-1990s, Greeks raised over 10 percentage points more from taxes on goods and services than the OECD, although the difference has roughly halved since then.

Which consumption tax?

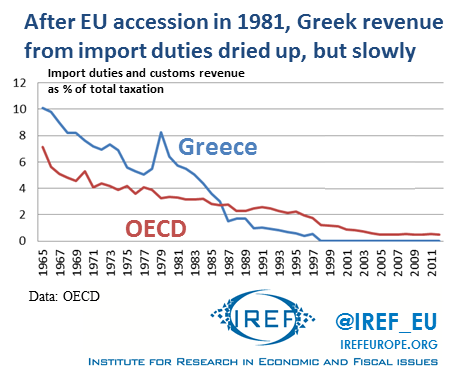

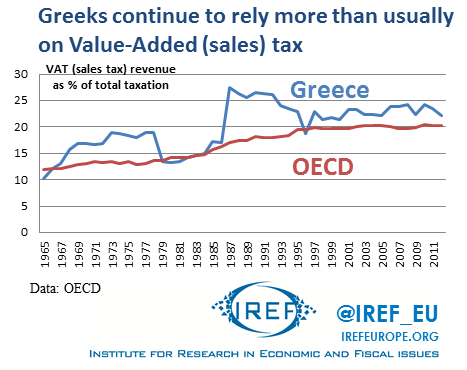

Breaking down the goods and services tax further, a statistics reveal not much difference in Greek reliance on specific excise duties (alcohol, tobacco, etc.). Most differences from OECD lie in import duties and sales tax (converted into VAT in mid-1980s in Greece).

Import tax revenue had to dry up after Greece entered a trading bloc with its main trading partners in 1981 – though it is perhaps surprising how slowly it did so. Short-sighted governments like to impose import duties in the hope of encouraging domestic “substituting” production, and the early gap helps to account for some of the missing Greek revenue.

Except for the early 1980s, Greece has relied more than was usual at the time also on VAT (sales tax) revenue.

What do Greek differences imply for its recovery?

Greek economy needs to start producing value again for Greeks to recover their pre-Euro standards of living. From that point of view it is perhaps praiseworthy that the government is effectively burdening production (through income taxes) comparatively less than consumption (through goods and services taxes).

However, there is a fly in the ointment. The government is already collecting disproportionately more of its revenue from the better enforceable source (consumption). If people remain pessimistic, rising incomes (relatively untaxed) may not convert into greater consumption (relatively taxed), and so the government is unlikely to raise much more money to pay off its debts, even if recovery happens.

Instead, perhaps the situation is ripe to make a bold step.

Is it time to get more tax revenue by lowering income taxes?

Economists frequently argue that lowering tax rates may increase revenue, but governments are scared that it won’t. Since the Greek government is already raising so relatively little from income taxes, it is not risking much and can afford to be bold, certainly bolder than other OECD countries.

So why not lower Greek income taxes? It may just work and increase reported income.