Central Banking – The Bank for International Settlements again Questions Prevailing Central Bank Policies.

The BIS has recently published two reports. In one, appearing to embrace the Austrian School of economic thought, it attributes the weakness of the present advanced economy recoveries to the disruptive effect of 40 years of multiple boom and bust cycles, which it blames on central bankers’ “asymmetric” policies. Asset price booms have been allowed to run and run, then central banks aggressively loosened monetary policies when each bust occurred. The BIS observes that if, after a bust, real interest rates are held too low for too long, the resultant credit booms cause severe problems for recovering economies. “Misallocation begets misallocation”. This happened both leading up to the Great Financial Crisis and in response to it. Debt has substantially increased. In the ten year period leading up to the GFC in 2008, household credit to GDP grew from 157% to 212% in the US, and similarly in Europe, where Spain’s credit grew the most: from137% to 274%. The other BIS report was its December quarterly review. It noted that markets had stabilised at the start of 2015Q4 following the August jitters triggered by China. As China’s stock market and currency stabilised, fears of an emerging markets crisis abated. However, the strong US jobs figures in November led to accurate expectations of the Fed raising rates, which in turn affirmed two concerns which drove financial market developments in the remainder of Q4 and at the start of 2016; a) divergent monetary policies among the advanced economies, and b) whether emerging markets will be able to cope with US monetary tightening. If China continues to impact western markets so strongly, it is worth calmly considering its prospects. We believe that the outlook for China is particularly acute, as China has built far more export capacity in recent years than other BRICS and encouraged domestic commercial and residential real estate construction and speculation. Longer-term, this new property and industrial infrastructure could prove to be of great value, but it needs to be financed in the interim, when it is unlikely to be profitable, and if a near-term investment bust were to occur this could prove a significant drag on the Chinese economy in 2016. Of course, with such a powerful government, a ‘bust’ could be magically prevented, but it is noteworthy that a government owned shipbuilder has recently been allowed to fail. Although the BIS was encouraged that, in November, emerging markets rode out the sharp repricing triggered by the dollar’s strengthening, no doubt the institution is worried by the events of early January. Renewed financial market wobbles in China resulted in US financial markets suffering their sharpest ever declines in the first week of a new year. Nonetheless the dollar strengthened again owing to its ‘safe haven’ status, as did the price of gold. Our view is that the BIS is broadly correct to focus on emerging economies. The seemingly abrupt end to the so-called commodity ‘supercycle’, associated with the previously rapid growth of the BRICS economies, is having multiple major consequences that will continue to play out in 2016. It was in the BRICS where advanced economy monetary stimulus from 2009 onwards had the most visible impact on growth, which soared in the aftermath. That positive growth cycle, however, is now complete. The stimulus, monetary and fiscal, has run its course. The BRICS individually now face a set of economic conditions at least as if not more challenging than they faced in 2009. How they deal with this situation, and how it affects the rest of the world, will be perhaps the dominant global economic theme of 2016. If the developed economies are able to respond to the current downturn with effective new stimulus, either fiscal or monetary, then this would bode well for the BRICS in 2016. However, policy flexibility is limited given the huge expansion of central bank and total economy balance sheets post-2008. A more realistic view is that stimulus, should it be forthcoming, will be less effective than in 2009-2013 and thus less supportive for the BRICS. Given their own potential balance of payments issues, as a group the BRICS are no longer in a position to provide meaningful new stimulus on their own. A weak recovery thus appears unavoidable. Although the recovery appears stronger in the US than in Europe, we noted that 2015 saw the most rapid turnover of chief financial officers at major US corporations. One quarter of companies in S&P 100 index announced CFO changes. Even the CFO recruitment firms were willing to speak openly about a consensus of strategy among the blue chip companies which appears inconsistent with traditional approaches to enhancing shareholder value via growth. Most of big companies display one or a combination of the following 3 strategies: a) cut costs and embrace technology; b) employ spare cash to increase dividends or buy back shares c) merge with, or sell the company to, a competitor So 25% of America’s leading companies are looking for CFO’s skilled in “financialization”.Banking – Misconduct now just part the “New Norm”, the Industry has won the Battle.

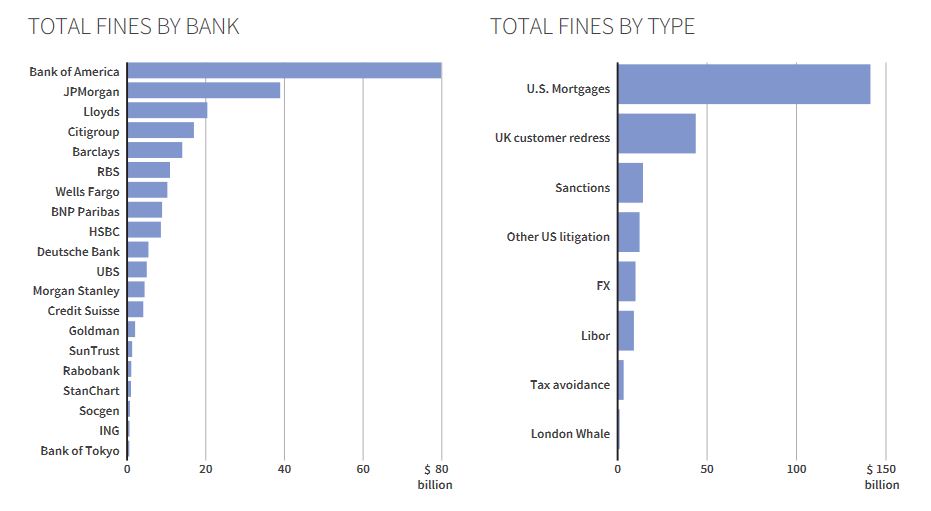

Even the staunchest supporters of the turnaround story struggle to explain the continuing stream of breaking misconduct stories. As at May 2015 Reuters published the following chart providing a broad overview of the $235 bn in fines and penalties paid by 20 banks. The chart reveals that about half of the total, $120 bn, are fines levied on just two US banks, Bank of America and JP Morgan. It is hard not to agree with defenders of banks who claim that regulators, encouraged by politicians, have been shifting the definitions of misconduct and using the threat of criminal sanctions against senior executives to extract large fines, especially in the US where banks – awash with cash – can easily afford them.

However, the detail behind the large US mortgage related penalties paints the integrity of banks in a very poor light. It also raises questions about the role of the US regulators who, since 2005 have had the power to file criminal charges against senior bank executives. The Department of Justice has jailed housewives, but not bankers, despite findings that almost every aspect of the mortgage lending process had been corrupted. Banks knowingly approved loans based on false property valuations, generated improper fees in the loan servicing business, boosted income further from unnecessary foreclosures, and committed securities fraud by misrepresenting the loan underwriting process to investors to whom packaged loan cashflows were being sold.

Why did the DoJ not use its powers under Sarbanes-Oxley, go up the chain of command and prosecute senior bank officers?

Consumer groups have pointed out that hardly any of the fines have compensated customers who lost out. Furthermore, the authorities’ focus on the media impact of large fines has distracted them from seeking to ensure that the underlying misconduct has been addressed.

In Europe the ECB has voiced concerns about European banks’ abilities to withstand US fines, fearing that meaty fines might trigger insolvency and test the new bank resolution mechanisms that have only this month come into effect.

Fears that the UK’s regulatory efforts to expose banking misconduct are being derailed by politicians surfaced at the end of December, when the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) announced that an expensive inquiry into the culture, pay and behaviour of staff in banking had been kicked into the long grass. The FCA denies political influence, claiming rather that a “traditional thematic review” would not help it achieve its objectives. It assured the public that nevertheless it would deliver “cultural change” in banking.

Our takeaway observation is that the banking industry, particularly in the stronger economies of the US and UK, expects to be left alone. The threats that misconduct attacks had posed may have brought big banking competitors closer together and one senses a degree of closer co-operation among big banks. We will watch with interest how banks respond to the recent US rate rise decision, and whether they pass on the benefit of higher rates to depositors. Unsurprisingly, some have already announced that they intend to leave deposit rates where they were and simply to pocket the difference between rates they pay and rates at which they can reinvest risk free. The justification of this widening of the Net Interest Margin (NIM) is that the spread has fallen from 3.9% in 2010 to 2.9% at end 2015. And yet with interest rates barely above zero, for banks to seek to restore NIMs to almost 4% raises eyebrows.

If there was a truly open market in banking and deposit taking services, NIMs on this scale could not exist owing to competition.

You can also download a printable version of the Newsletter.

jan2016.pdf

The chart reveals that about half of the total, $120 bn, are fines levied on just two US banks, Bank of America and JP Morgan. It is hard not to agree with defenders of banks who claim that regulators, encouraged by politicians, have been shifting the definitions of misconduct and using the threat of criminal sanctions against senior executives to extract large fines, especially in the US where banks – awash with cash – can easily afford them.

However, the detail behind the large US mortgage related penalties paints the integrity of banks in a very poor light. It also raises questions about the role of the US regulators who, since 2005 have had the power to file criminal charges against senior bank executives. The Department of Justice has jailed housewives, but not bankers, despite findings that almost every aspect of the mortgage lending process had been corrupted. Banks knowingly approved loans based on false property valuations, generated improper fees in the loan servicing business, boosted income further from unnecessary foreclosures, and committed securities fraud by misrepresenting the loan underwriting process to investors to whom packaged loan cashflows were being sold.

Why did the DoJ not use its powers under Sarbanes-Oxley, go up the chain of command and prosecute senior bank officers?

Consumer groups have pointed out that hardly any of the fines have compensated customers who lost out. Furthermore, the authorities’ focus on the media impact of large fines has distracted them from seeking to ensure that the underlying misconduct has been addressed.

In Europe the ECB has voiced concerns about European banks’ abilities to withstand US fines, fearing that meaty fines might trigger insolvency and test the new bank resolution mechanisms that have only this month come into effect.

Fears that the UK’s regulatory efforts to expose banking misconduct are being derailed by politicians surfaced at the end of December, when the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) announced that an expensive inquiry into the culture, pay and behaviour of staff in banking had been kicked into the long grass. The FCA denies political influence, claiming rather that a “traditional thematic review” would not help it achieve its objectives. It assured the public that nevertheless it would deliver “cultural change” in banking.

Our takeaway observation is that the banking industry, particularly in the stronger economies of the US and UK, expects to be left alone. The threats that misconduct attacks had posed may have brought big banking competitors closer together and one senses a degree of closer co-operation among big banks. We will watch with interest how banks respond to the recent US rate rise decision, and whether they pass on the benefit of higher rates to depositors. Unsurprisingly, some have already announced that they intend to leave deposit rates where they were and simply to pocket the difference between rates they pay and rates at which they can reinvest risk free. The justification of this widening of the Net Interest Margin (NIM) is that the spread has fallen from 3.9% in 2010 to 2.9% at end 2015. And yet with interest rates barely above zero, for banks to seek to restore NIMs to almost 4% raises eyebrows.

If there was a truly open market in banking and deposit taking services, NIMs on this scale could not exist owing to competition.

You can also download a printable version of the Newsletter.

jan2016.pdf