„I hope that our government, more enlightened and more liberal than in the past,

will be in the future the true friend of the best and noblest cause that exists;

and that the name of England will forever be dear to the Greeks.“

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in a letter to Alexandros Mavrokordatos (February 22, 1825)

It was New Year’s Day of 1822 when modern Greeks officially introduced themselves to the world. After fighting for ten months against the Ottoman Empire, they controlled the greatest part of Classical Greece and the Aegean Sea.

Nobody expected that. Every single power in Europe, including Great Britain, was convinced that the Sultan would crush the uprising in a few weeks – and some certainly hoped so. In post-Napoleonic Europe, upsetting the status quo was a mortal sin punished by the Holy Alliance. After only five years since the Battle of Waterloo, a wave of liberal revolutions began in the Iberian Peninsula. During the Congress of Laibach (modern day Ljubljana) in early 1821, the participants were shocked when they realized that liberalism had contaminated not only the Italian peninsula but even the Balkans. The conservative Gazette de France expressed eloquently their fears in a mid-April 1821 editorial on Greece: “Six hundred leagues are no great distance, now that liberalism navigates with full sails, and is making the tour of the world.”

All the liberal revolutions of 1820-21 failed with one exception. It was short of a miracle. Greeks did not have an ally, the European powers (like Orthodox Russia) remained neutral at best or were scheming against them like Austria. The spiritual leader of the Orthodox Christians, the Patriarch of Constantinople, was executed by the Ottomans on Easter Sunday of 1821, while the leader of the Revolution, Alexandros Ypsilantis (an aide-de-camp of the Russian Emperor), surrendered to the Austrians and was incarcerated for more than six years.

“The whole world saw us as crazy. But if we had not been crazy, we would not have started this revolution. If we had been sensible, we would have seen that we do not have ammunition, cavalry, artillery, powder kegs, cartridges. We would have compared our power with the power of the Turks.” Theodoros Kolokotronis was right. He was formerly a rebel-brigand and a mercenary in the British army, and emerged as the natural military leader of the Greeks. Thanks to his ingenious strategy, he singlehandedly defeated the local Ottoman forces first and then the strong Ottoman army which invaded the Peloponnese in 1822. Because of him the Revolution was consolidated, and the Great Powers realized that they could not sweep the Greek question under the rug.

It took another man, an intellectual totally different from Kolokotronis, to build on the latter’s military success and develop an original foreign policy based on a sophisticated geopolitical vision. That man was Alexandros Mavrokordatos, an intimate friend of the Shelleys, who hosted Byron in Missolonghi. Mavrokordatos managed to persuade the Europeans that the Greeks were neither the puppets of Russia nor Carbonari, and that their war was for independence and religious freedom. He systematically promoted the idea that the Greek Revolution was an opportunity for Great Britain, rather than a threat.

George Canning, the new foreign minister of Great Britain after Castlereagh’s suicide, did respond to Mavrokordatos’ signaling. The Greek merchants and shipowners were a natural ally of the English, whereas an independent Greece could become a buffer state against Russia and a loyal ally. Great Britain could benefit from this Revolution after all.

When the Greeks introduced themselves into the world, they declared their political goals. They fought not only for national independence but also for their integration to their rightful place, Europe. They were determined to become a pillar of the West in South-Eastern Europe; to establish a modern state with a rule of law. And they succeeded against all odds. Today, the modern Greek state includes every single area where the Greeks revolted in the Spring of 1821. From the recognition of its independence in 1832 to the middle of the 20th century, the territory of Greece has been almost tripled in size. From the very beginning the Greeks embraced constitutionalism and in the last quarter of the 19th century Greece became one of the first and most durable liberal democracies in Europe, with one of the longest parliamentary histories in the world, a record number of national elections and universal suffrage for men since 1844.

Canning was vindicated. Greece did become the most dependable ally of Great Britain for a century. It is one of the few countries which was consistently on the “right side of history,” in the First and the Second World Wars (the first country who defeated the Axis forces, i.e., Mussolini, in 1940), as well as in the Cold War. Greece was an economic success story despite the setbacks (civil war, two short-term dictatorships, political polarization), one of the few countries in the world which escaped the middle-income trap: from 1929 to 1980 the average annual rate of growth of income per capita was 5.2% according to the Statistical Office of the United Nations.

Despite the recent economic crisis (disposable per capita income dropped 42% from 2009 to 2015), liberal democracy remained strong, and Greece remained a part of Europe. The neo-Nazi party which entered the Parliament in 2012 lasted seven years and in 2020 its leaders were convicted by a criminal court.

Despite the scars left by the economic crisis, the current government managed to steer Greek society during the pandemic rather well. The measures adopted in Spring 2020 minimized losses and the fast (unprecedented for Greek standards) building of digitalized procedures allowed quick vaccination.

As Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote in the preface of Hellas (1822): “The modern Greek is the descendant of those glorious beings whom the imagination almost refuses to figure to itself as belonging to our kind, and he inherits much of their sensibility, their rapidity of conception, their enthusiasm, and their courage.”

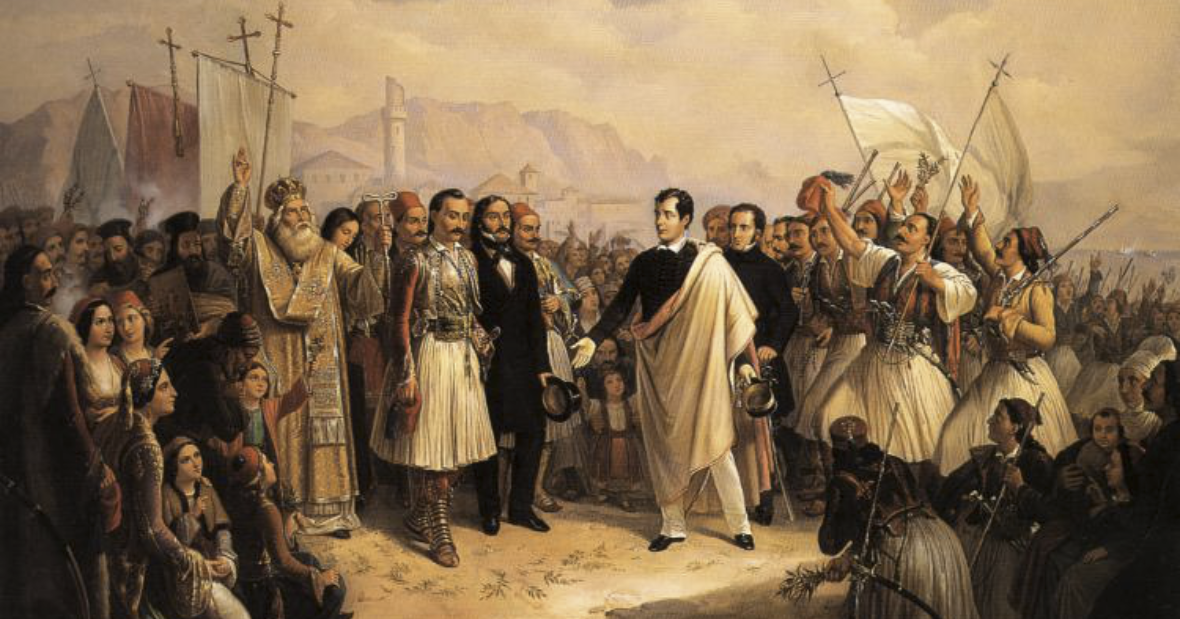

Photo (edited): Theodoros Vryzakis, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons