New retail tax in Hungary discriminates big business, which just happens to coincide with the finance minister’s nationalistic interest. New retail tax in Czechia favours big business, which just happens to coincide with the finance minister’s business interest. Curious thing, Coincidence…

Europeans’ grocery shopping experience varies a lot. Five largest retail chains in Denmark account for 87% of the country’s grocery market while in Italy they only make less than a quarter of all sales.

There is of course no “natural” or optimal concentration. National market with just two competitors can be more competitive than one with 10 (they could all be regional monopolies). History of retail practice, population density, domestic agriculture or even religion may matter. (There is more weekend outlet shopping time in less religious countries.)

It is not the role of a government to influence whether citizens buy from big or small companies. Yet two new tax policies by two central European governments are doing just that. Interestingly, they discourage big business in one country and encourage it in the other.

Hungary: tax policy discriminating big business

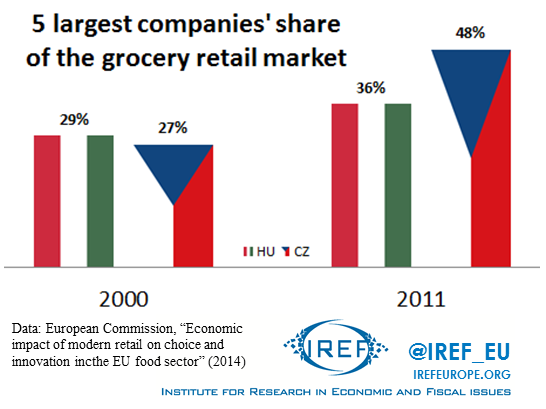

The market share of the 5 largest grocery retailers increased in all EU countries between 2000 and 2011, according to a recent EU Commission report. In Hungary it did so relatively little, however, rising from 29% to 36%. In the Czech Republic, by contrast, it increased to 48%, having started below Hungary. (For interest, Poland went from 7% to 26%, Belgium from 51% to 76%, etc.)

All grocery retailers in Hungary used to have to pay an extra 0.1% tax on their turnover. Officially the proceeds were to finance regular food chain health inspections, but as usual, any surpluses or deficits of such fund were simply connected to the general government budget. Effective 2015, the Hungarian government now drastically changed the tax, erasing it for small- and retaining it for medium-sized grocery retailers. Those with turnover above €160 million are now, however, charged progressively increasing rates up to 6%. Since this is 6% of turnover and not of profits, it is pretty draconian. Needless to say, food chain inspections are not that expensive to run all of a sudden and therefore the large retailers would just end up financing general government.

First such taxes are due at the end of this week. 2 weeks before the deadline, the EU Commission issued an injunction on collecting the tax until it carries out “in-depth investigations”. The Commission is worried that the low rates for small retailers constitute forbidden state aid – so presumably it may bizarrely end up recommending to actually increase the tax rate on the small retailers, in order to “remove obstacles to competition”.

This would be wrong. It is high taxes that are the main “obstacle to competition”.

Czech Republic: taxing in favour of big business

As noted above, the Czech grocery retail market is becoming dominated by “big business” much faster than the Hungarian one. Changes to the tax system (now being passed through the Parliament) will in all likelihood speed up this trend, quite arbitrarily.

At the moment, Czech grocery (and other) retailers pay their VAT in the usual way. At the checkout, purchases are recorded in the shop’s computer system, and at certain intervals (depending on the country), the accountant sends off the VAT to the Finance Ministry, based on what was sold over the preceding period.

From next year, the Czech Republic will be the second EU country (after Croatia) to implement a compulsory system of governmental electronic automatic reporting. All cash registers in the country are to be connected to the internet. (“Use your mobile internet if you are selling at a farmers’ market!”). The moment you buy anything (with cash or otherwise), the transaction is immediately and automatically “ratted out” to the tax authorities by the cash register, without any possible human intervention. If the seller doesn’t enter the transaction into the register (and print from it a receipt for the customer), she is in for a very hefty fine.

How does this favour big business? The system will be expensive for businesses. Not only to implement (new sophisticated cash registers, printers) but also to run (online connectivity, software upkeep). Obviously larger retailers will be better able to afford them because the technology scales up cheaply.

In addition to disadvantaging small businesses, the new tax policy will struggle to even pay for its own costs. In Croatia there was a short boost to VAT revenue after the 2013 introduction of cash registers connected to the tax authority, but it is evaporating once the initial period of fear has passed.

The idea that there is some way of collecting 100% of taxes due – and all that government needs to do is to be an even bigger Big Brother – is just wrong.

Why do the two governments do it?

The official explanation is presumably “to raise more revenue”. Indebted EU countries want to be seen as “doing something which does not cut spending”. In reality, the policies may end up collecting less as some businesses are driven under or abroad.

However, in both the Hungarian and Czech cases, a more sinister explanation offers itself.

The Hungarian discrimination of big companies will also be discrimination of foreign companies. (Domestic retailers are much smaller.) This is in tune with the government’s professed nationalistic ideology. We already reported last year on the anti-foreign impact of the new Hungarian tax on media advertising.

By contrast, Czech governments are generally not particularly jingoistic. However, its current finance minister personally owns all the large companies in the upstream food chain, from raw chemicals, fertilizers and agriculture to food production. Nothing in Czech pubs or grocery stores is sold which one of his companies did not at least directly help produce. Large producers generally find it easier to deal with large sellers. Trade war is costly, and long term “understandings” are easier than if there is a vibrant undergrowth of small retailers.. The new Czech tax policy may therefore turn out to be not a governmental policy, but a policy of the finance minister. Government revenue may be a smokescreen for imposing costs on the less controllable segment and getting real time information on everybody.

Both the Hungarian and Czech cases show that tax policy can often have alterior motives.