«From now on our nation’s answer to this great social challenge will no longer be a never-ending cycle of welfare: it will be the dignity, the power, and the ethic of work. Today we are taking an historic chance to make welfare what it was meant to be: a second chance, not a way of life…The new bill restores America’s basic bargain of providing opportunity and demanding in return responsibility».

These words were pronounced by American President Bill Clinton when he signed the Personal responsibility and work opportunity reconciliation act (August 22, 1996). They followed Clinton’s promise to «end welfare as we know it», and marked the transition to a new concept of welfare assistance, requiring responsibility as a necessary condition for public support. One year later, and consistent with the perspective put forward in the Jobs Study published by the OECD in 1994, Tony Blair’s New Labour Manifesto followed Clinton’s lead by claiming that «…Rights and responsibilities must go hand in hand, without a…option of life on full benefit» -.

It might seem a little odd that the principle of responsibility was forcefully put forward by political leaders with a left-wing political orientation. In fact, the emphasis on responsibility was consistent with the at-the-time current mantra delivered by those who strived to save egalitarianism: any discourse on inequality must distinguish between situations due to circumstances – which go beyond individual responsibility and require compensation by the society – and situations due to lack of effort, for which no compensation is required.

Theoretical thinking and the features characterising many advanced countries (high unemployment, high public debt, etc.) in recent decades led to stressing the role of personal responsibility in what has become the mainstream perspective to welfare policy design since the ’90s. In particular, the emphasis on responsibility entails an obligation to stay actively in the labour market. Individuals are entitled to support only if they register for job action plans or provide evidence that they are actively looking for a job.

However, this kind of contractual approach to welfare policy design has raised a number of questions. Some doubts relate to whether these requirements actually encourage people to move from unemployment (or inactivity) to work. General economic conditions matter, and there is no evidence that the sanctions potentially applicable have a significant effect. First, because sanctions are usually negligible. Second, because public officials in charge of providing sanctions – that is the reduction, suspension or cancelation of the existing benefits – use their discretionary power to vary these in accordance with the general economic conditions. Moreover, in many cases carrots (tax credit related to job acceptance, for example) may function better than sticks.

Stricter eligibility criteria: are they enough?

In theory, unemployment benefits can have desirable consequences, since they provide a safety net to individuals. Yet, they can also backfire. More generous benefits might lead to longer unemployment duration and higher aggregate unemployment. This is why recipients of unemployment benefits are required to be available for work, actively look for work, take up suitable job offers or register for active labour market programmes (ALMP).

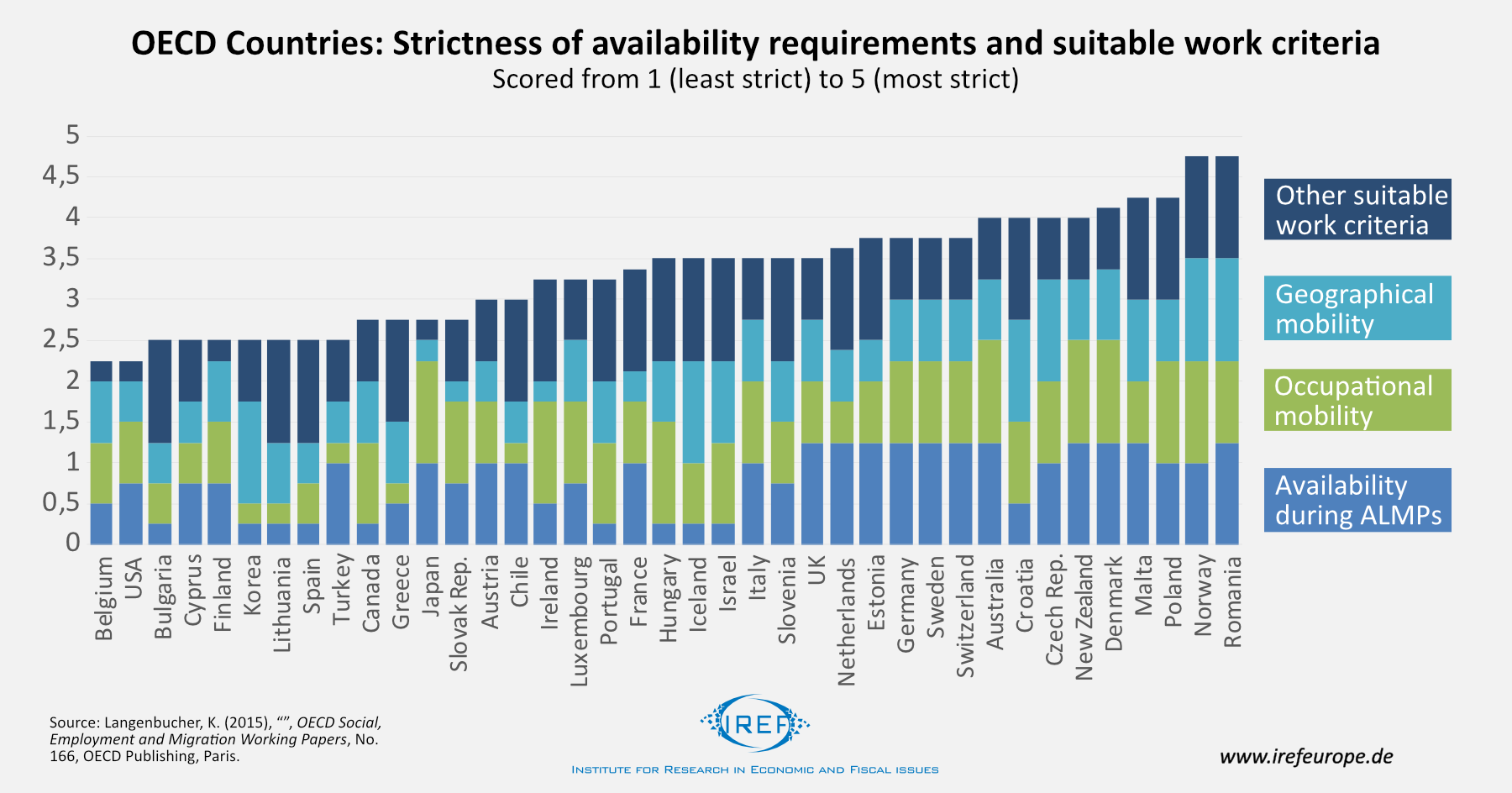

Eligibility criteria include the definition of suitable work (types of work that must be accepted if offered), rules concerning active job search and sanctions for non-compliance. The OECD has collected and analysed some interesting evidence. For example, figure 1 displays the nature of the availability requirements and suitable work criteria across a number of countries.

Despite a common tendency to adopt stricter requirements for benefits claimants in recent years, the differences across countries are significant. Some economies, such as Poland, Norway, and Romania allow the unemployed just a few valid reasons for refusing job offers, and require participants in active labour market programmes (ALMPs) to be available for work. By contrast, other countries like Belgium, the United States and Spain, allow refusals of job offers for a broad range of reasons and do not require availability during most ALMPs. In Australia, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom, ALMP participants must remain available and actively look for work.

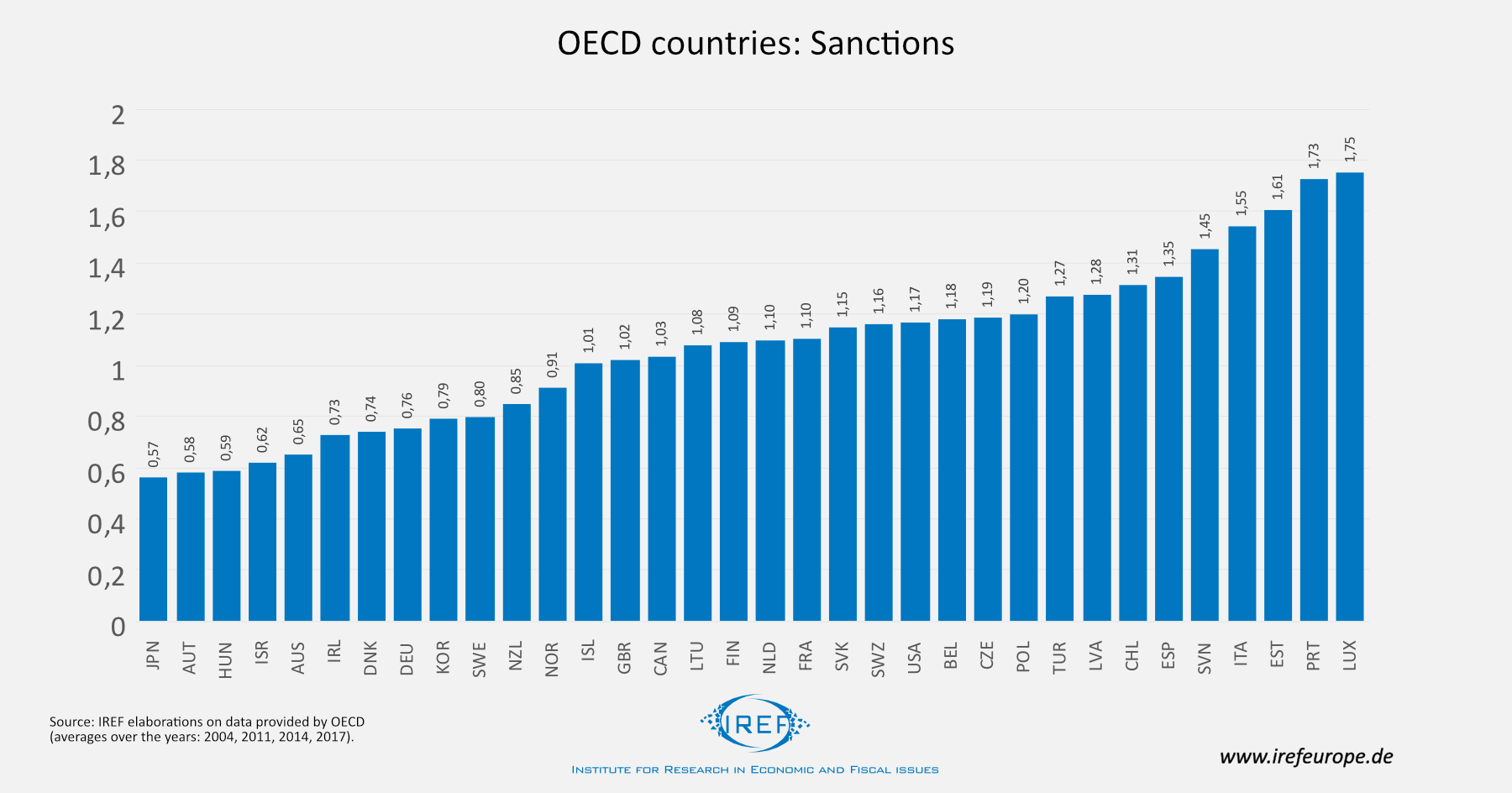

As far as sanctions are concerned, they regard reduced benefits in the presence of voluntary unemployment or other similar behaviours: declining a job offer, or refusal to attend counselling interviews or join active market programmes. Figure 2 ranks the OECD countries according to the severity of sanctions, on a 5-point scale.

Overall, a composite indicator (named Overall strictness of eligibility criteria) summarizes eleven items that add up to a measure of the eligibility criteria: they include the Strictness of availability requirements and the suitable work criteria, as in Fig 1 above, and also other aspects related to monitoring and sanctions. This index was developed by Danielle Venn in 2012, is based on insights provided by the Danish ministry of Finance in 1998, and is currently used by the OECD.

Let us consider the deviations of the strictness-of –sanctions index from the OECD mean (Fig. 3, blue line). It appears that the differences across countries are not very marked (for each country, the blue line is close to the OECD mean, which corresponds to the zero line). However, differences increase when one considers the Overall strictness of eligibility criteria indicator (red line).

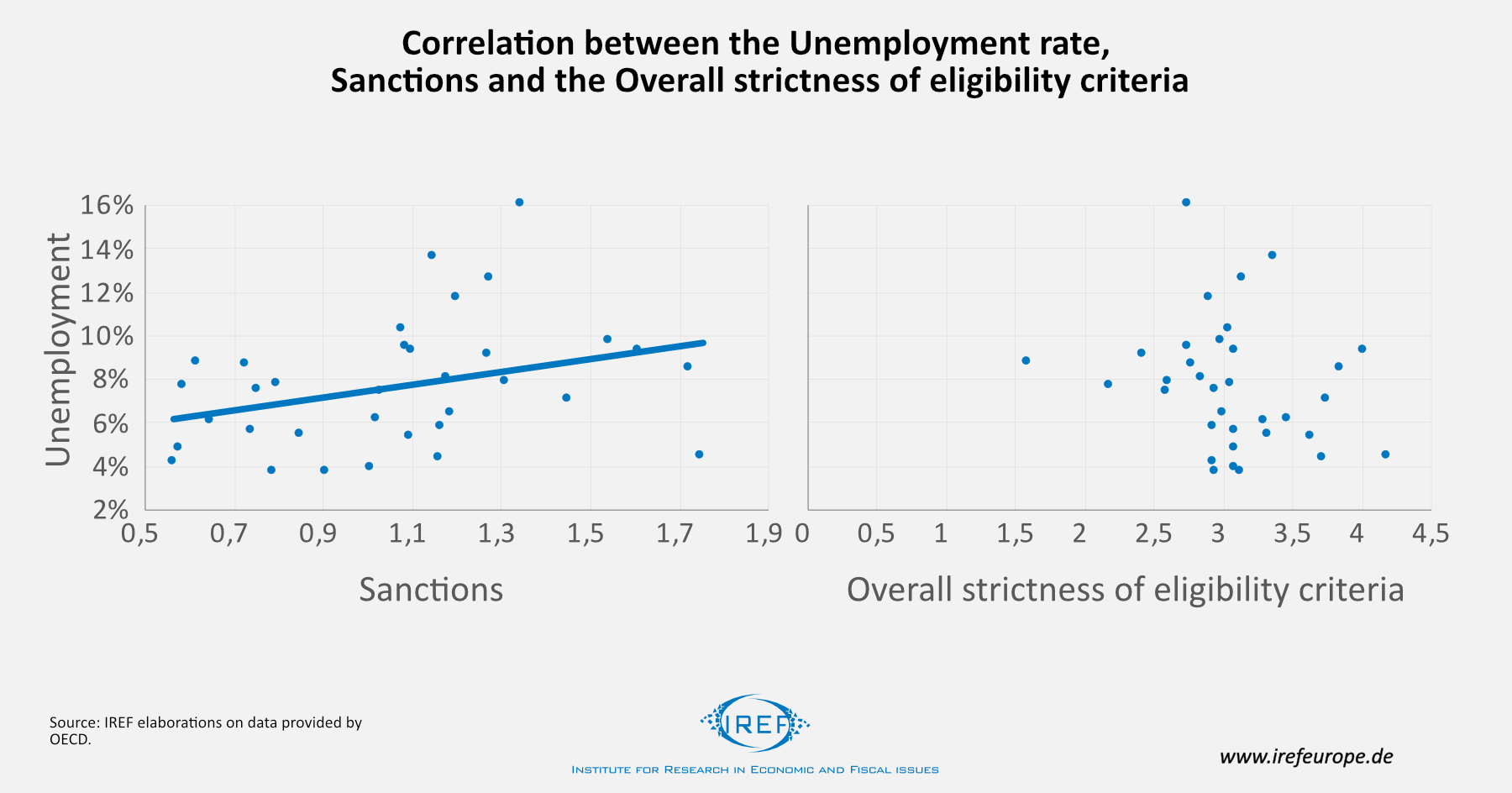

We conclude by drawing attention to the relationship between the unemployment rate, the Overall strictness of eligibility criteria indicator, and the sub-indicator related to sanctions (35 OECD countries are observed over the period 1998-2017). Figures 4a and 4b show that countries characterised by stricter or more credible sanctions are also those experiencing high rates of unemployment.

This suggests that sanctions are a way of limiting government expenditure, rather than an effective way of reducing unemployment. No correlation is found between the rate of unemployment and the strictness of the eligibility criteria.

As pointed out by Danielle Venn in a 2012 OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper, all these indices reflect the strictness of the rules. However, one should not neglect to observe that public employment offices have some discretion in interpreting them in practice. In poorly-working labour markets, offices may be more willing to apply exemptions, and monitoring may be constrained by the presence of a high number of applicants and the reduced number of vacancies. In a word, stricter criteria may turn out to be less strict than meets the eye.