On December 17, 2010, a young Tunisian by the name of Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest against police harassment. His act triggered a wave of revolts across the Arab world as people rose against authoritarianism and poverty. The fall of Ben Ali’s regime in Tunisia after 23 years in power generated enormous expectations. People throughout the region hoped to end injustice and corruption, and start moving towards freedom, democracy and economic prosperity.

Many scholars consider Tunisia the only success story amid the Arab countries involved in the 2011 uprisings because Tunisia seemed to be the only country that emerged as a democracy. However, in 2013 the interim coalition government led by the Islamist Ennahda Party came under accusation for being incompetent and power-hungry. The opposition’s fears were confirmed by the assassination of Chokri Belaid, a secular politician. The crisis escalated further in July 2013, when 65 members of the National Constituent Assembly momentarily walked out of the assembly when another opposition politician, Mohamed Brahmi, was assassinated.

On July 30, the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) called for conference to resolve the crisis. Three other civil society groups, the Tunisian Order of Lawyers, the Tunisian Union of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts (UTICA), and the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH), joined to form the National Dialogue Quartet. In December 2013, partly as a result of the Dialogue, a new government led by Mehdi Jomaa saw the light. The national dialogue helped place the country back on the pathway toward balance after the uprising in 2011.

Yet, the economic conditions of the country have hardly changed since the interest groups that had characterized the old regime successfully opposed all kinds of economic reform. Those who had hoped that democracy could make a difference are disappointed. Political participation fell from a high of 68 percent in the 2014 parliamentary elections to 42 percent in 2019.

Not surprisingly, therefore, in July 2021 tensions erupted. When the last government led by Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi enforced measures to deal with Covid-19, tens of thousands of Tunisians defied the lockdown and protested against Mechichi’s government and the political class in general. President Kais Saied suspended parliament, dismissed the prime minister, and announced he would temporarily rule by decree. In a word, democracy was put on hold.

Tunisia’s political crisis originates from a decade of economic failure

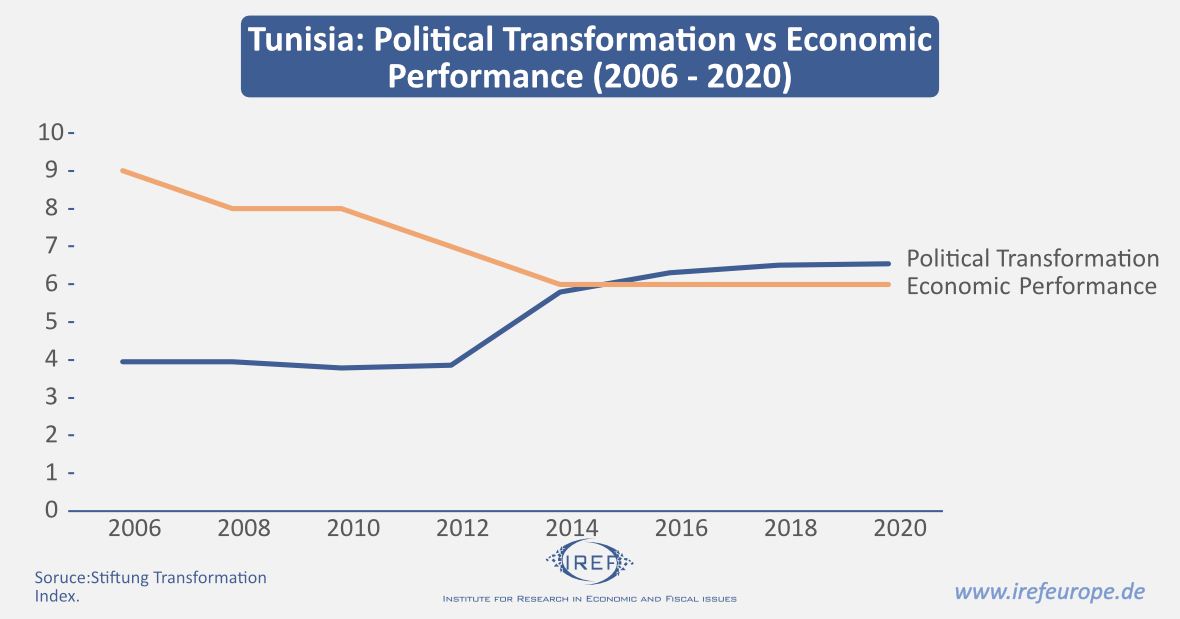

Indeed, despite the transition to partial democracy and significant advances in political and civil freedoms, endemic corruption and fragile enforcement of property rights are still inhibiting economic development and political stability. Some indicators, such as the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index (BTI)[[the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index (BTI) reports data from two years earlier. Thus, the 2020 report uses 2018’s data, and the political scene in Tunisia back then was not in a critical situation as it is today.]] describe Tunisia’s failure in the last decade.

As mentioned above, most Tunisians judge the revolution by considering economic performance, which has not improved. Since 2011, households’ incomes have fallen by a fifth; the Tunisian Dinar has lost half of its purchasing power; unemployment is currently at about 18%, with youth unemployment at more than 35%, up from 29% in 2010. Corruption persists, and the government budget deficit has now reached record levels at around 11%.

Tunisia is known for its active civil society. However, the government’s effort to please all major actors ended up slowing down economic transition. As a result, thousands of Tunisians left the country. Last year, at least 13,000 Tunisians risked their lives trying to reach Italy by boat. [[COVID-19 fallout drives Tunisians to Italy despite deportations – Migration, The New Humanitarian, Layli Foroudi, 1 September 2020]] Others simply committed suicide.[[Suicide by self-immolation in Tunisia: A 10 year study (2005-2014) – National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), by Mehdi Ben Khelil , Amine Zgarni , Malek Zaafrane, Youssef Chkribane, Meriem Gharbaoui , Hana Harzallah, Ahmed Banasr, Moncef Hamdoun, Nov 2016]]

The bottom line is that nowadays, more and more people start regretting Ben Ali’s “good old times”, when unemployment and tensions were lower, and they forget that those good old times featured extensive corruption and systematic violations of human rights. This climate of discontent towards the world of politics and disbelief in the democratic process explain why President Kais Said has been able to put democratic principles aside, take over the country and enforce a one-man rule regime.

Why did Tunisia fail?

In a sentence, political transition is not enough. Tunisians failed to develop free-market institutions. None of the two major parties Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes have engaged in significant economic reforms, enforced budgetary discipline, and reined in privileged interest groups. Nidaa Tounes has been torn by internecine tensions, while Ennahda has been suffering from bad reputation. In addition, both Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes needed money, and were not in a position to reject funds by interest groups. Of course, these offers came at a price.

Put differently, democratic rule requires much more than regular elections. It requires robust institutions and free-market oriented economic reforms, to reduce the role of the state and make room for private (unsubsidized) business.