Introduction – Bulgaria’s recent announcement

On 17 February, Bulgarian finance minister Rositza Velkova announced that, rather than continue as planned with the full, formal adoption of the euro on 1 Jan 2024, Bulgaria would postpone its Eurozone entry date for at least one additional year. The official explanation is that Bulgaria is still lagging behind some of the EU’s requirements for Eurozone entry and that these cannot realistically be met during the course of 2023.

This is understandable given the current instability of the Bulgarian government. The recent caretaker, minority government did introduce several bills associated with required euro preparations, including important insurance legislation, but it was dissolved before they could be fully debated and passed.1

Bulgaria has now endured a series of inconclusive elections, with no stable ruling coalition emerging. It is not clear on what timetable this might change. Hence it is possible that Bulgaria may be facing an even longer wait for eventual euro accession.

The challenges go beyond domestic Bulgarian politics

Even if a more stable government assumes power during the coming year, it is unclear whether that will indeed ensure that Bulgaria is both able and willing to join the euro in 2025 or beyond. In this regard, it is worth considering the recent experience of Croatia, which formally adopted the euro on 1 Jan this year.

As we wrote in January edition, Croatia’s decision to join the euro was in effect made many years ago, and the timetable and roadmap to entry were not characterised by domestic government instability. It is worth asking the question, however, whether Croatia would make a similar decision today, given how the European landscape has changed in several key respects.

First, unlike in years prior, inflation is now elevated and ECB interest rates are rising. January Eurozone inflation was 8.6%. In Croatia, it was 12.7%. (One reason for Croatia’s higher rate is likely to be merchants ‘rounding-up’ prices when converting from kuna to euro, rather than rounding down.) In Bulgaria, inflation is even higher, at 16.4%.

Higher inflation also characterises non-euro countries, such as the UK, Sweden and Norway, but at a minimum, non-euro members have a degree of national latitude how they choose to respond. Croatia has now lost that flexibility. While policy discretion can be abused, leading to a spiral of inflation and currency debasement, that needn’t be the case. The UK, Norway and Sweden have all kept their exchange rate volatility via-a-vis the euro in tight historical ranges in recent years and inflation rates have also been comparable.

New ECB powers might be of concern

Of greater concern could be that the ECB has assumed powers in recent years that give it a tremendous amount of de facto fiscal policy influence. The new stability mechanism [link NL September 2022], designed to prevent euro members’ relative borrowing costs from soaring to levels that could threaten the transmission of monetary policy across the Eurozone, could be used to favour certain countries over others. It could be used to encourage countries to follow certain fiscal guidelines, for example austerity budgets; or it could be used to punish those that don’t.

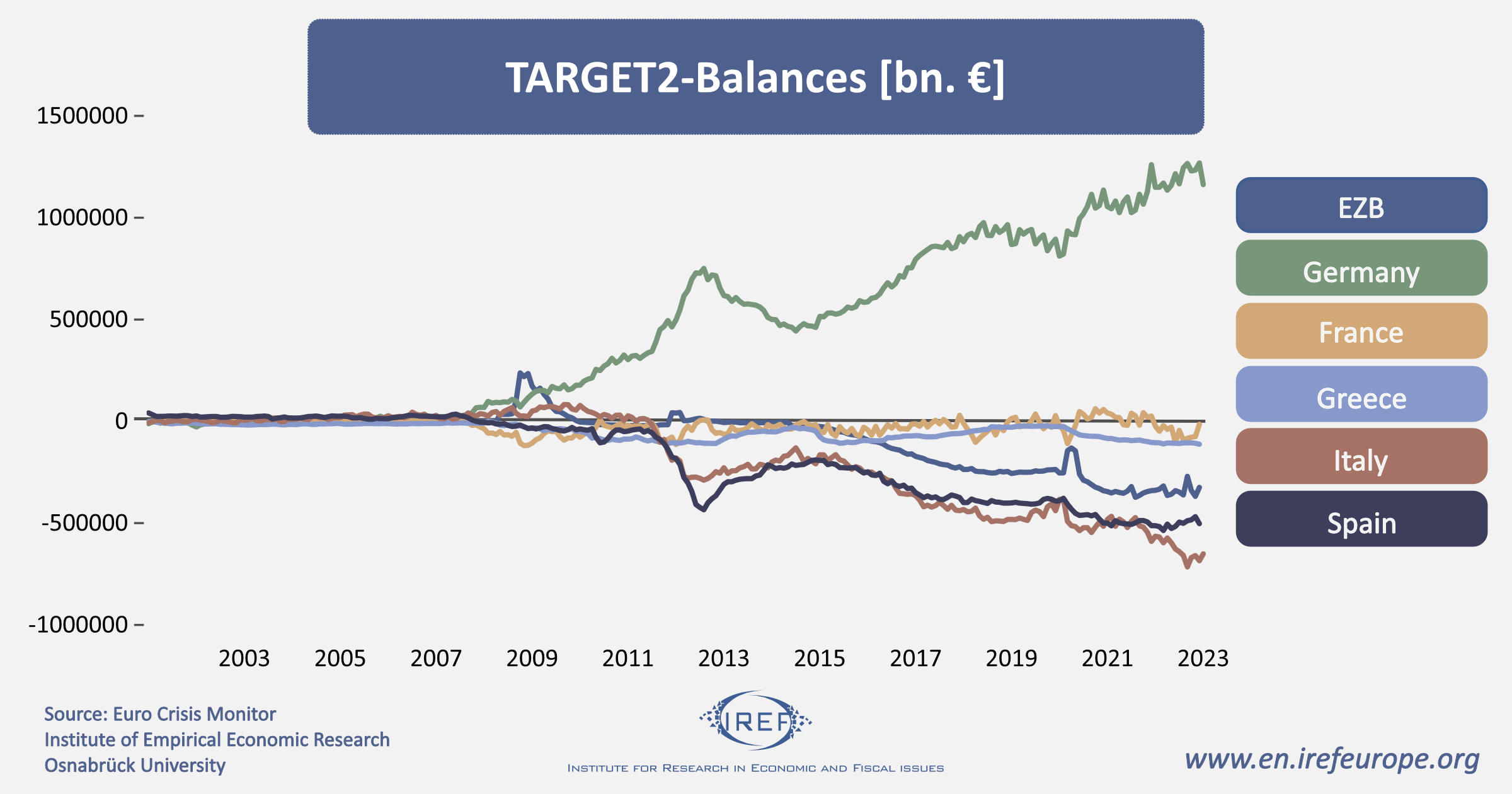

Notwithstanding the above, the Eurozone’s cross-border Target2 imbalances continue to grow. The temptation at the ECB will be to do even more in future, if necessary, to prevent capital flight and monetary transmission breakdown in member countries. What additional powers it might seek to assume are anyone’s guess, but given the pattern of behaviour established to date, it would be surprising were they not to try.

Thus, not only do the original, theoretical euro risks remain. Recent developments have meaningfully changed how the Eurosystem works in practice. Why would Bulgaria want to commit to euro membership, something from which it could not extricate itself without tremendous disruption, unless it were convinced that the single currency project was sustainable long-term?

Do the benefits still outweigh the possible costs?

No doubt there is still strong support in Bulgaria for eventual accession to the Eurozone at some point in future. The primary reasons are:

- Access to Free Money. By moving from outside the tent to inside, Bulgaria could benefit by likely having access to funds such as the ¢750 bn EU Next Generation Fund, more than half of which will be disbursed by way of grants, not repayable loans.

- Target2. Bulgaria’s banks would also be permitted now to overdraw their accounts with the Eurozone settlement system. They could follow Italy and others and use the settlement system as a new source of unlimited and never to be repaid credit from Germany and the Netherlands, principally.

- Geopolitics. With Black Swan events such as COVID and the Ukraine war popping up, it is easy to understand why a smaller fringe country such as Bulgaria would decide that the geopolitical benefits of full club membership trump the risks that joining the euro would bring more potential downside than upside in future.

That there are potential benefits of euro membership is undeniable. But the potential downside has grown alongside various crises and the ECB’s expanding powers. The balance has shifted somewhat.

Domestic Bulgarian politics to remain in flux

It is unrealistic to think that there will be a meaningful, lasting settlement of the deep divides in Bulgaria’s politics anytime soon. Yes, a stable ruling coalition may emerge. But a powerful opposition will remain. Bulgaria, historically stuck in a tug-of-war between east and west, remains so today. The euro is seen by some Bulgarians as pulling the country dangerously close to the west and potentially limiting flexibility to engage with the east. Such cultural divides are not easily surmounted in short periods of time. Sometimes they even take generations.

There is, however, good reason for Bulgaria not to worry too much about remaining on the fence in the meantime. The central bank is under good governance and purchases only the highest-quality assets—German government bonds—to provide for its monetary base. Moreover, the currency board introduced by Bulgaria in 1997 to provide for currency and, by extension, monetary and financial stability, has been a resounding success and remains in place today.

The banking system is relatively underleveraged when compared to most Eurozone member countries. The Bulgarian National Bank (the central bank) requires banks to maintain liquidity reserves with it of 10% of qualifying liabilities (deposits and their ilk). In the rest of the Eurosystem this ratio is 1%. As for capital strength, the big players in Bulgaria are foreign owned. It is feared that, on joining the euro, the likes of Unicredit (Italy), KBC (Belgium) and Raffeisenbank (Austria) will repatriate surplus capital from their Bulgarian subsidiaries.

Bulgaria may be one of the poorest countries in Europe. But it is also at present one of the least indebted, least leveraged and least financialised. Eurozone membership for Bulgaria could bring about a substantial releveraging in terms of both liquidity reserves and capitalisation, potentially destabilising its relatively sound banking system. That may give some pause for thought.

Bulgaria can afford to wait, should it choose to do so. Those considering investments in the country should not be deterred by any reluctance or delay in joining the euro, which might not happen for years.

Broader implications

Although it is a small economy with limited political influence, Bulgaria sets an example that euro membership is not required for economic stability, either within the EU or without. In a post-Brexit world, one in which the UK never joined the euro, nor Sweden for that matter, it remains clear that the single currency remains an option, rather than a requirement.

While quite a different economy from all of the above, it is worth noting that tiny Switzerland, surrounded and overwhelmingly dependent on EU trade, has also managed to maintain economic and financial stability in recent years. Inflation is running at a mere 3.3%. That might be high by Swiss standards, but as a major energy and food importer, it is understandable.

Indeed, Switzerland’s recent experience demonstrates that which politicians and economic officials sometimes prefer to deny: Inflation is not some bogeyman hiding in the closet, occasionally making a sudden, unexpected, frightening appearance.

No, inflation is a policy choice. Years and years of easy ECB monetary policy were a choice. The excess liquidity thereby created may have been sequestered into bank recapitalisations, asset market inflations and other non-CPI directions for years. But amidst the negative supply shocks of Covid restrictions and the Ukraine war, that excess liquidity has found its way into the largest consumer price inflation since euro inception.

1 https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/bulgaria-gives-up-its-goal-to-join-eurozone-in-2024/