In mid-January, the European Parliament voted a resolution to phase out the use of palm oil as a component of clean diesel by 2021. This is a ban only on one ingredient, all other diesel “cleaners” are not treated. In particular, the Parliament asked the Commission “to take measures to phase out the use of vegetable oils that drive deforestation, including palm oil, as a component of biofuels, preferably by 2020”, so that the “contribution from biofuels and bio liquids produced from palm oil shall be 0 % from 2021”. The reasons: deforestation of rainforest in palm oil exporting countries, and the parliamentary ambition to fulfill the Paris accord on climate change and the UN 17 sustainable development goal. The resolution was promoted by Czech MEP Katerina Konecna of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left, originally a member of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia.

The Committees’ attitude towards the ban was mixed. The 225-page file of parliamentary debate reveals the following positions. The lead committee on Environment, Food Safety and Health was most radical, insisting that “the progressive and long-term development of human society is one of the cornerstones of the EU, and it must therefore also be an aspect of our decision-making process in cases such as the palm oil issue.”

The consulting committees (on International Trade and Agriculture and Rural Development) had a more elaborate opinion, especially the Trade Committee: it de facto opposed the ban, suggesting a wait-and-see approach, provided “sustainable forestry” is maintained.

The EU policy to promote clean diesel was justified about ten years ago again by considerations of clean environment and managing the climate change. It resulted in the adoption of the Renewable Energy Directive 2009/28, which introduced a subsidy for the use of biofuels and set a goal of 10% “clean” diesel usage in the Union by 2020. As shown by the Index Mundi statistics, the incentivized demand by the EU led Indonesian, Thailand’s and Malaysian farmers to more than double the production of palm oil.

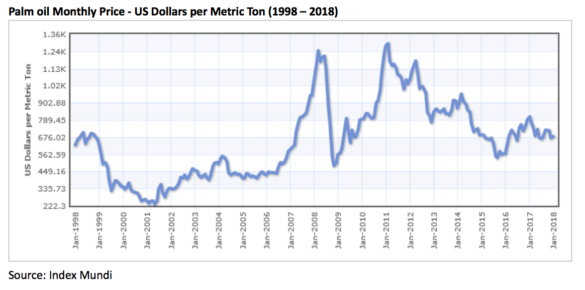

The graphs below shows that prior to the Directive, prices went up almost exponentially, but then fell due to growing supply. Since 2009, they have never reached again the 2007-2008 level (above $ 1,000 per metric ton), and in the last five years have fluctuated at around $ 700 per metric ton, with a declining trend.

–

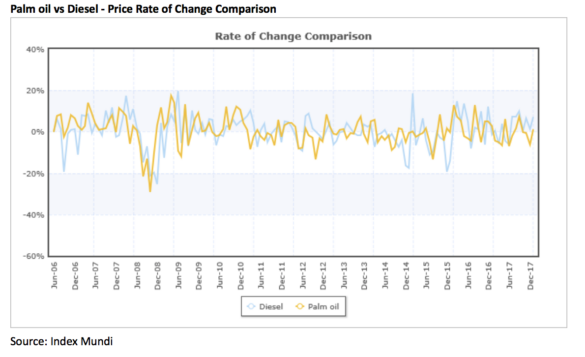

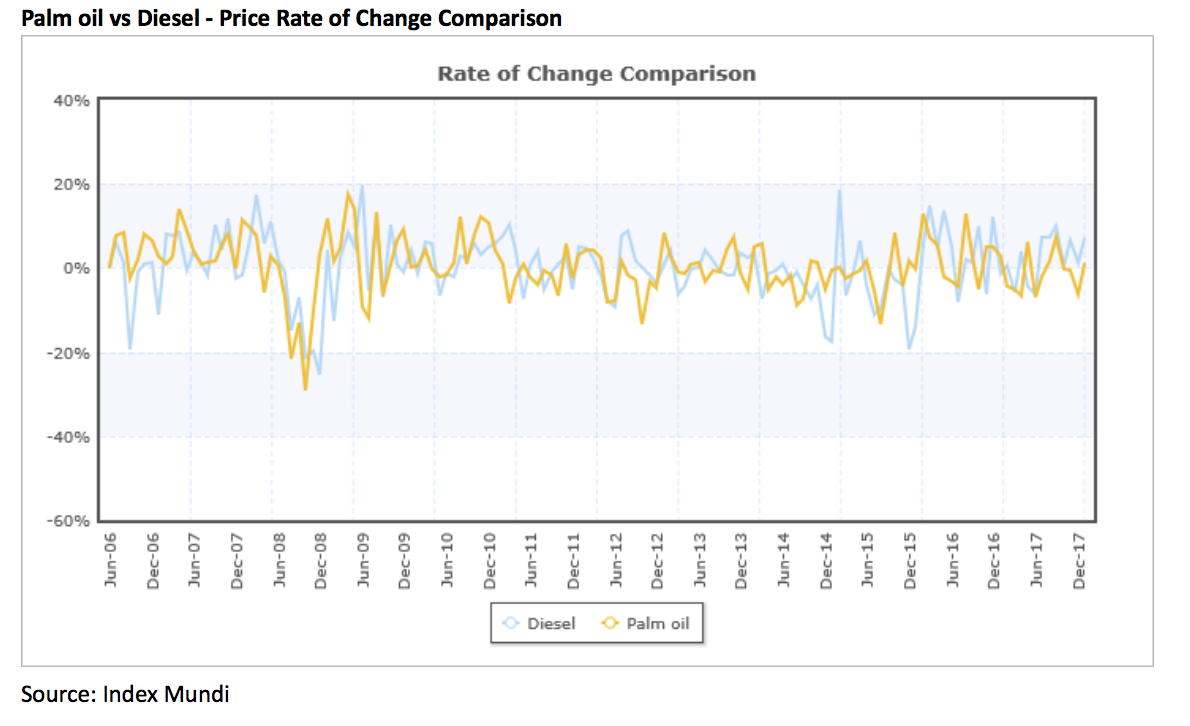

The Parliament now blames palm oil production as cause for deforestation, thus incurring “high cost of cultivating the cheap vegetable oil”. However, since the oil is used in diesel fuels, it is logical to assume that its price is correlated to that of diesel. Here is the correlation from 2006 to present day. The coefficient is relatively high (0.39).

The deforestation was, arguably, partially caused by the EU policies. By 2013, the EU has become the second largest importer of palm oil for clean diesel.

The surge in demand stimulated supply, and thus, allegedly, led to more plantations. But deeper background analysis suggests that the cutting of the rain forest has been linked to technological development and that the solution to the “problem” depends on markets and on the allocation of property rights.

The logging of rain forests in palm-oil exporting countries (the combined sale of the three countries mentioned earlier is 90% of the world total in 2017) started 100 years ago, when trees were cleared for rubber plantations, then for mining and resettlement of poor households (in 1950 and 1960s), and it went on until 1980. After 1980, the production of palm oil started, and was hailed as a “global cornerstone”, a “progressive and long-term development of human society”.

Ten years ago, Malaysia adopted a plan to increase the acreage of protected forest by 5%. According to a World Bank report of November 2017, “despite the complex legal and institutional structure, Malaysia is a success story in delivering efficient land administration services”. The WWF admits that the rain forest currently covers almost 60% of the country’s territory. Yet. It argues that it is not enough.

There is little progress in forest user rights in Indonesia. But in 2015, the Center for Indonesian Policy Studies, proposed to fight deforestation by strengthening communal and private property rights.

Once again, the current motion of the European Parliament to phase out palm oil from biofuels, championed by Ms. Konecna and Green and Left MEPs, has unintended consequences. For example, it bans only palm oil in bio fuels, but keeps subsidizing all other ingredients of biofuels. This approach raises issues about political discrimination and lobbying in favor of suppliers of other ingredients, at the expense of the palm oil producers, supposedly about 1.2 mln farmers globally.

The resolution of the European Parliament violates the WTO principles, and it may discredit the difficult balance of global trade rules. Deforestation, the key justification for the resolution is not properly analyzed, it is short-sighted and it takes into account neither the market forces, nor the diverse situations in palm oil producing countries. The proposed policy is likely to hit many farmers in not-so-rich countries. Sooner or later, those very EU lawmakers and central planners, like Ms. Konecna, will complain about global inequality and propose subsidies to compensate for the damage they had imposed on others.

The silver lining is that Parliamentary resolutions are not binding. One hopes that the European Council will opt for a no-policy-change approach, and leave the matter to be resolved by itself, by market forces and property rights, like the Indonesian institute suggests. Eventually and gradually, the entire policy of subsidizing diesel, or any other similar policy, will be abolished.