For several decades, labour market experts and economists have been advocating what now seems to become real: in 2020, Germany’s new immigration act will come into effect. The ‘Skilled Immigration Act’ is supposed to make immigration of qualified, non-EU citizens significantly easier. In the future, qualified workers without academic degrees will have immigration opportunities which were previously open to university graduates only. Moreover, they will no longer be legally at a disadvantage compared to German nationals and EU citizens.

While German home secretary Horst Seehofer sees this as a steppingstone towards successful immigration policy, experts are arguably less enthusiastic. In light of the high remaining barriers to immigration – and of some new ones –, one doubts that the 25,000 additional immigrants per year that the German government expects will actually make their way into the country.

In fact, this reform reveals how deeply Germany perceives immigration as a threat to its social security system. If one considers the experience with asylum-seeking migrants in the previous years, this fear is not entirely unjustified. Yet, the lessons drawn are flawed. Rather than restricting migration to Germany, reforms should aim at offering immigrants easier access to the labour market.

Lower barriers for skilled workers, but tighter language requirements

The Skilled Immigration Act affects almost exclusively non-EU citizens. This Act was accompanied by the “Orderly Returns Act”, under which refugees will be allowed to look for a job over an extended period. Yet, one fears that only few people will take advantage of this option.

In the past, non-EU citizens could get a visa to accept a job offer or spend a maximum of six months looking for a job. This option, however, regarded only university graduates or workers with skills in areas characterised by a recognised labour deficit – e.g., in the health sector or in information technology. By contrast, in the future this possibility will be open to all foreign nationals who received training recognised in Germany. Moreover, in most cases employment of a non-EU national will no longer be dependent on whether an unemployed German or EU national is available for the job.

However, the new legislation requires that non-EU nationals wishing to immigrate will have to know basic German – even those with a degree, who previously needed to provide little to no evidence of their language abilities. The Institute for Employment Research, the research institute of Germany’s Federal Employment Agency, estimates that an individual needs on average 800 study hours in order to achieve the required CEFR level B1. Since German is only rarely studied as a foreign language outside the EU, these language requirements are in fact a significant immigration barrier.

High hurdles remain

While equal treatment of qualified personnel with and without degrees is desirable, the Skilled Immigration Act does not bring about fundamental reforms of the existing legal architecture. These changes ease labour market migration only marginally.

First, in order to discourage benefits-motivated immigration, job-seeking non-EU citizens have to fund themselves until they find a job and are not allowed to exercise a profession that does not match their formal qualifications. Even part-time employment that meets the workers’ qualification is only permitted for ‘trial shifts’ with a weekly maximum of ten hours. In other words, immigration is only feasible for people who can financially sustain the job search without temporary employment by the side; and for those who succeed in getting a job matching their formal qualification within six months. Entering the labour market via apprenticeship or internship programmes, a common situation for qualified Germans and EU nationals, is forbidden.

Second, non-EU nationals are only allowed to work if the qualifications they received are recognised as equivalent to apprenticeships or degrees received in Germany. A lack of formal qualifications can only be compensated with practical experiences in certain positions in the field of information and communication technology. This is the only exception to the prohibition of employment on the basis of partly recognised qualifications. Likewise, acquiring qualifications while already employed is only permissible under special circumstances. According to the Institute for Employment Research, these strict rules are the most significant barrier to immigration, since Germany is one of the very few countries with a dual education system.

Third, the intended creation of legal and organisational security for employers and immigrants is weakened by the fact that in some cases — migrants coming from specific countries or working in specific professions – it is still possible to make hiring conditional on the presence of Germans or EU citizens available for the job.

Skilled immigration barely expected to rise

Overall, the remaining and the new requirements are still significant barriers for non-EU citizens willing to migrate. These barriers are serious, because individual strengths and weaknesses are not weighed up against each other, a common feature characterising points-based immigration systems. In particular, higher professional qualifications cannot balance out worse German skills. How many people will overcome all these hurdles at the same time?

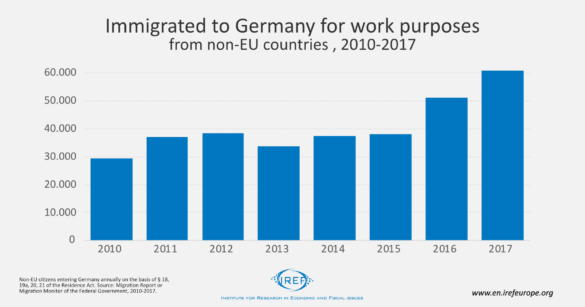

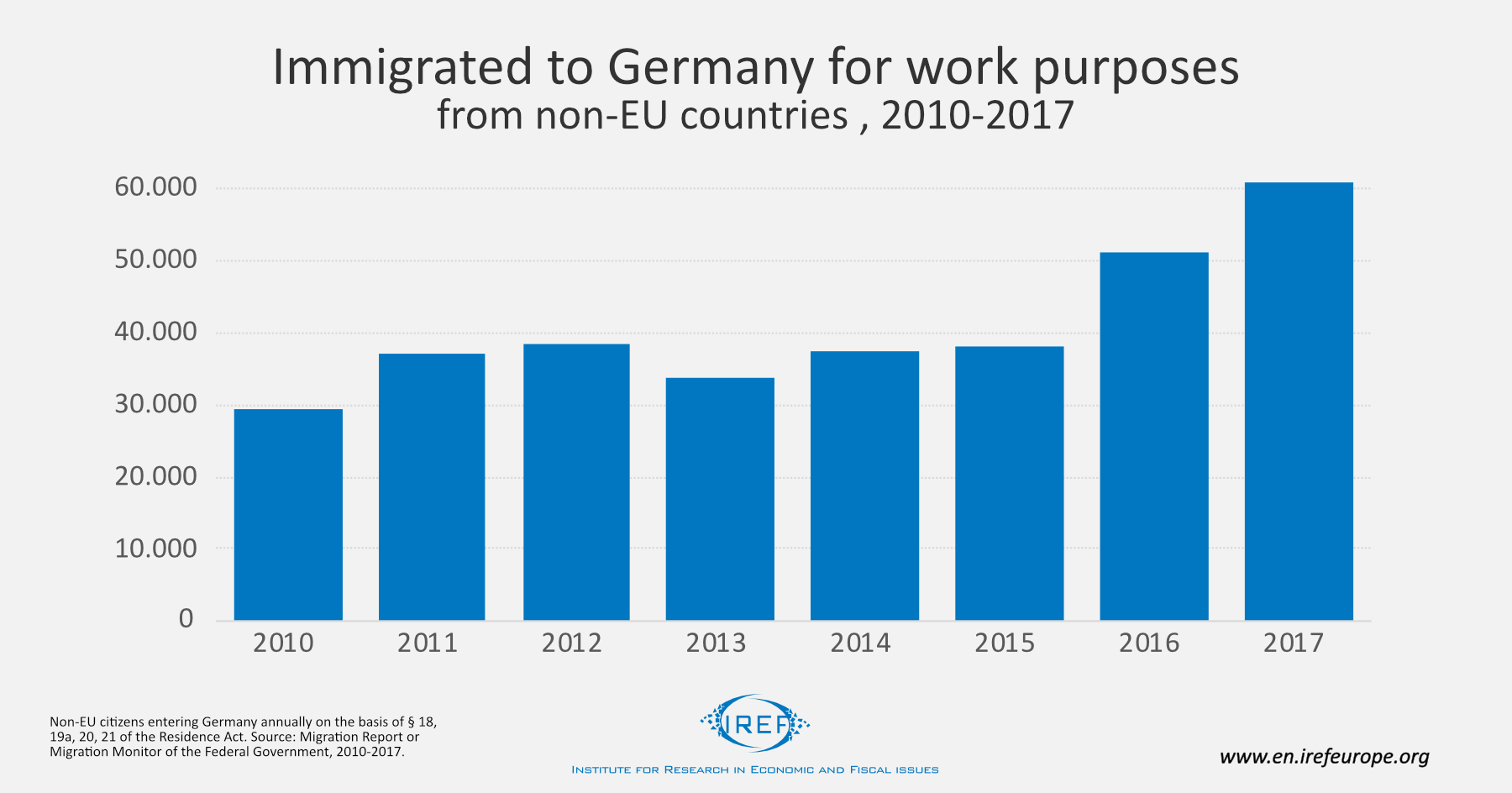

Previous experiences with highly educated and skilled workers in ‘deficit jobs’ migrating from non-European countries are not encouraging. In 2017, 60,000 non-EU citizens went to Germany to work; this makes up only 11% of all immigrants. Over 90% of all residence permits issued for this purpose were given to non-EU citizens who studied at a German university. According to the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, German embassies worldwide issued only 2,100 visas for the purpose of job-seeking in 2017.

Missing the benefits of immigration: collateral damage of welfare policy

The faint-hearted reforms of the German immigration law illustrate that the central issue of German migration policy remains unresolved: politicians do favour labour market immigration, but they are also afraid of the consequences on the welfare system. Since fundamental reforms about the scale of – and access to — the benefits remain on paper, all efforts regarding immigration policy are limited to those less likely to be a burden on the welfare state. Indeed, it would be preferable to reform the welfare system and the labour market instead of de facto excluding potential immigrants. Higher thresholds for temporary occupations should replace minimum wage legislation; and hire-and-fire rules should be weakened for all employees, especially for immigrated skilled workers. This is the simplest and most effective way of reducing the risk of free riding on the German welfare state without denying immigrants entry into the country.