In early 2011, an unprecedented wave of political uprisings swept the Arab world. It was the so-called Arab Spring. Protesters in several Arab countries took to the street and demanded changes in governments, freedom, bread, and dignity. The main slogan was “the people want to bring the regimes to an end.” The reasons that inflamed the uprisings across the region included excessive levels of corruption, police brutality, lack of political freedoms, low levels of income along with high income inequality, high levels of youth unemployment and, last but not least, dictatorial regimes.

Most of the early protesters, like Mohamed Bouazizi, the street vendor who set himself on fire on 17 December 2010 in Tunisia and became a catalyst for the Tunisian Revolution and the wider Arab Spring riots, were all people living in destitute conditions, victims to arbitrary laws, barriers to entrepreneurial activities, and pervasive encroachments on political freedom and private property. Regrettably, those protests eventually brought very little results, but the underlying conditions that inspired them are still present, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made them worse.

The status quo: the conditions that lead to the Arab spring continue to exist

At present, 55.7 million people in the region need humanitarian assistance, including 26 million forcibly displaced. [[The Impact of COVID-19 on the Arab Region An Opportunity to Build Back Better – United Nations, July 2020]] Extreme poverty has been on the rise since 2011. The World Bank’s biennial Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report finds that the rate of extreme poverty in the MENA region rose from 3.8% in 2015 to 7.2% in 2018, with more than 20 million people living on less than US$1.9 per day. [[World Bank. Poverty and shared prosperity 2018: piecing together the poverty puzzle. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018.]] These increases in extreme poverty are linked to civil wars in Yemen, Libya, and Syria and to the instability of several other Arab neighboring countries such as Egypt, Lebanon, Algeria, and Tunisia, which provide a clear example of failed transitions.

The intense rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran over spheres of influence has also contributed to exacerbating regional hostilities and instability in the region. It has turned the civil conflicts in Syria and Yemen into extended bloody proxy wars with no end in sight. Iran’s role in Iraq and the powerful Shiite militia group Hezbollah in Lebanon have also fed internal tensions in these countries.

Ostensibly, the Arab Spring flopped. It failed to deliver political freedom and economic opportunities to the Arab population. Moreover, the counter-revolutionary measures ended up strengthening the incumbent regimes or allowed new repressive regimes to replace the old ones. Something is moving, though. In 2019, massive demonstrations took place in Algeria, Iraq, Sudan, and Lebanon.

New uprisings in the not too distant future

As mentioned above, the underlying social-economic and political factors that triggered the 2011 Arab spring continue to provoke unrest across the region. The high rates of youth unemployment that were prevalent ten years ago continue to this day. They average between 25 and 30 percent across the region and exceed those of any other region in the world.[[International Labour Office, “Global Employment Trends for Youth 2017: Paths to a better working future, 2017.]] Women’s participation in the labor force is also poor (20 percent in 2019). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic is making things worse, e.g. by breaking down global supply chains and leading to rises in food prices.

Actually, food prices are a good predictor of future unrest in the Arab region. They do not trigger riots themselves, but create a fertile ground for social unrest. When people cannot feed themselves or their families, they have nothing to lose and disorder breaks out.

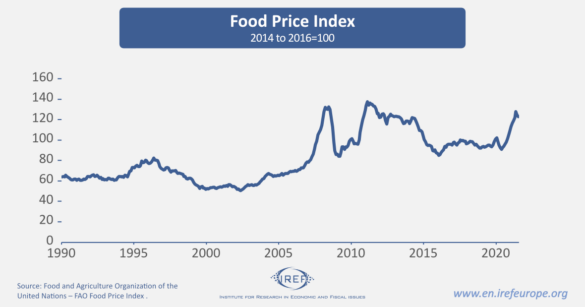

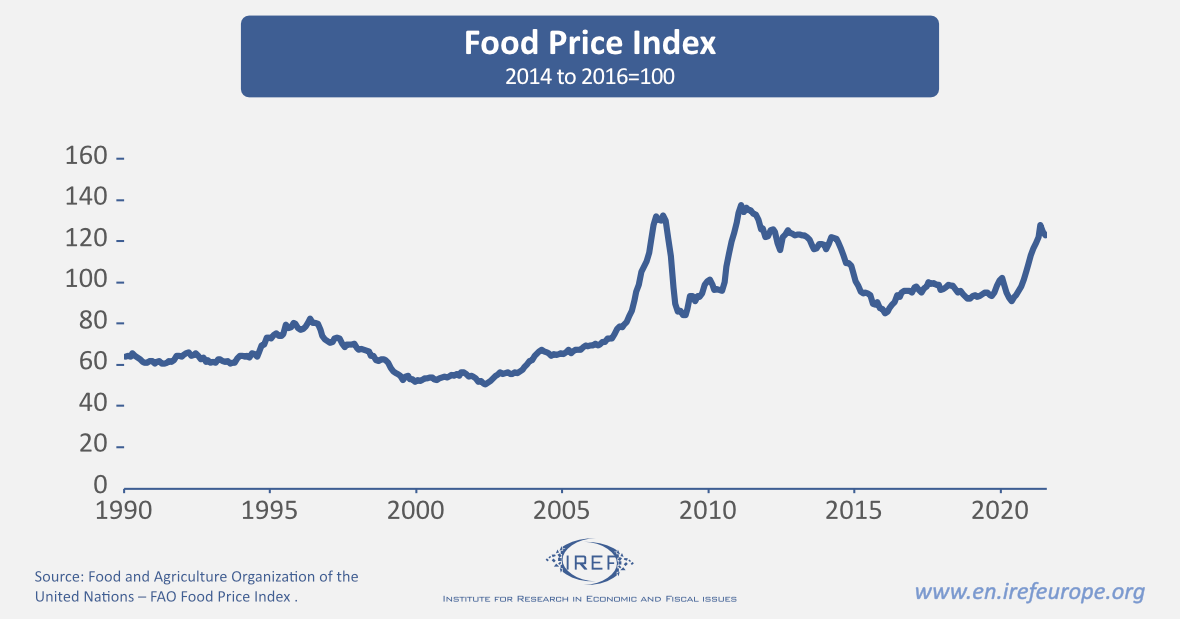

Although there is not much agreement about what led to the explosion of the Arab spring, in 2011 the rise in food prices almost certainly played an important role. In 2010, the FAO Food Price Index soared by 17%. and today, food prices across the Arab region have risen back where they were ten years ago. In most countries, price hikes have been moderate (5% or less), but in Algeria, Egypt, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, prices of staple food have increased by more than 20 percent during since early 2020. [[MENA Crisis Tracker – Office of the Chief Economist, Middle East and North Africa, The World Bank, 27 June 2021.]] According to the FAO’s Food Price Index, lower stocks of wheat and vegetable oil and – more generally — disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic have pushed global food costs to the highest level in a decade. These are likely to rise further during the rest of this year (+14%) and in 2022.[[Commodity Markets Outlook – World Bank Group, April 2021.]]

To summarise, the Arab region may be on the edge of a new era of rising food prices and shortages that could easily set off serious political unrest. Arab leaders have long recognized the link between hunger and turmoil. In response, they have resorted to subsidies and price caps. It won’t work. The region relies very much on imported food. Price caps make sure that imports drop, while tight budgetary constraints limit the size of the subsidies. Thus, shortages will emerge and (black-market) prices will soar.