Populism Italian Style and some bizarre ideas about representative democracy came to an end when prime minister Giuseppe Conte resigned and Mario Draghi took his place. Draghi has become a national hero and people have been changing their minds. They no longer trust that bombastic stories could replace lack of content, and that MPs can be appropriately selected through a fanciful internet-based contest where candidates would flaunt their qualities and air their promises.

In truth, it was not difficult to predict that the populist coalition supporting the first Conte cabinet – an alliance between the League and the Five-Star Movement (5SM) that took power in 2018 – was inadequate to handle the economic situation. However, the coalition supporting the second Conte cabinet did not fare much better: the alliance between the 5SM and the pro-European Democratic Party founded by Romano Prodi in the ‘90s proved unable to find the necessary compromises and ran into trouble. This is not surprising. The 5SM had promised to shake and reshape the entire Italian power structure. By contrast, the DP represents the very bulwark of the incumbent pressure groups. To make things worse, former prime minister Matteo Renzi quit the DP, formed his own party and withdrew his support to the coalition. Conte’s government had to resign. As a result, the Italian President Sergio Mattarella asked Draghi to try to form a new government.

Draghi succeeded in finding the support he needed. This was not surprising. Most of the incumbent Italian MPs do not wish early elections. A recent Constitutional reform reduced the number of parliamentary seats by one third. Understandably, most incumbent MPs fear for their seat and for the lavish stipend that goes with it. There is however another reason that explains resistance to the early elections: the Next Generation EU money is round the corner, and all MPs want to make their presence felt and possibly have a share of the pie.

Conte’s mistakes

Indeed, the amount of money (209 billion euros) that the EU will hand out to Italy is huge: it exceeds 10% of the Italian GDP, and 80 billion will be provided as grants. No wonder it will play a crucial role.

However, in order to take advantage of those resources, Italy will have to submit a detailed spending program. Here is the problem. Towards the end of 2020, the Italian establishment began to fear that Conte did not have the skills and personal prestige to meet EU demands and ensure that those 209 billion would eventually arrive. To top it up, Conte contributed to the mess by bypassing parliament and creating a parallel superstructure of some 300 “experts”: a structure that would have diluted responsibilities and opened the door to the most disparate interest groups. President Mattarella was clearly alarmed: the loss of image and the economic consequences of such failure would have been devastating.

A man of last resort

The above contributes to explaining why the Italians greeted Draghi as the man of providence, while foreign observers were relieved at seeing a man of prestige at the helm. Indeed, most people currently believe that Draghi’s international image and technical abilities will be more than enough to deal with Covid-19 and give momentum to the agonizing Italian economy. A man of last resort.

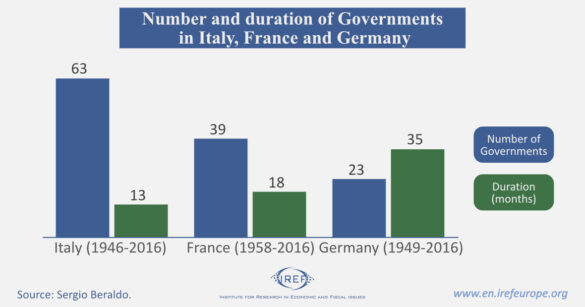

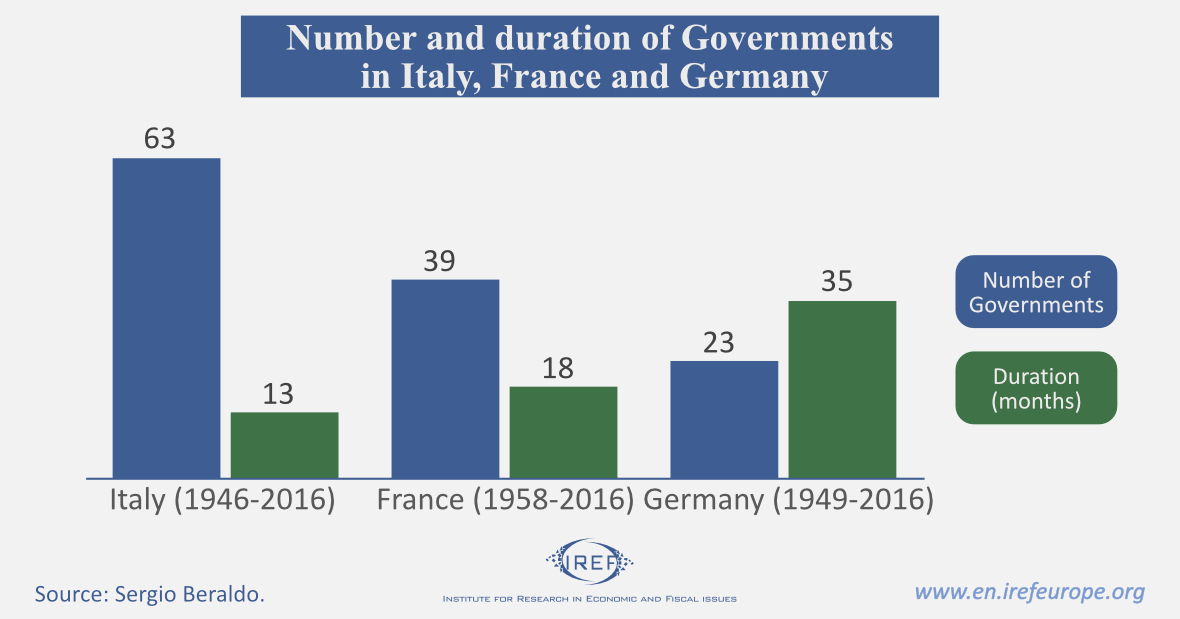

Yet, Draghi’s task will not be a piece of cake. He will make choices that will not necessarily meet unanimous approval, and it is not clear how parties and factions will react. Since the end of the second world war, Italy has had 69 governments, one every 13 months on average. This is typical of a country where public affairs (res publica) are often considered a way of promoting local interests and satisfying pressure groups. The data available do not allow precise comparisons. Yet, Figure 1 below may be enough to illustrate the Italian anomaly.

Italian governments do not last much. The main reason is that they result from fragmented parliaments. Fragmentation allows even small parties to have a strong blackmailing power: they can tip the balance, and usually do not hesitate to do so.

In the 1990s, a new electoral law succeeded in reducing party fragmentation. Yet, the law was later gradually amended and Italy slowly returned to where it started. Politicians were of course happy, but the reversal ensured that Italy has now found it difficult to cope with serious problems – like Covid-19 – and to make effective use of the financial resources available. To make a long story short, factions are ready to raise their voice once again, and they will definitely play a role in determining what comes next. Draghi can indeed show up as the puppeteer. Yet, it won’t be easy.