As a reaction to COVID-19, governments are making extensive financial aid available. However, beyond helping out households and companies in need, aid also attracts opportunists. Because of this, the OSCE is expecting corruption to increase. Yet, this danger differs across countries, even within Europe, where corruption is less problematic than in other regions. In Scandinavian countries, corruption within the civil service affects people’s lives very mildly. In some countries of Eastern and Southern Europe, the situation is more complex but not hopeless, as shown by recent encouraging developments in a number of countries, e.g. Estonia.

Perception of corruption: data

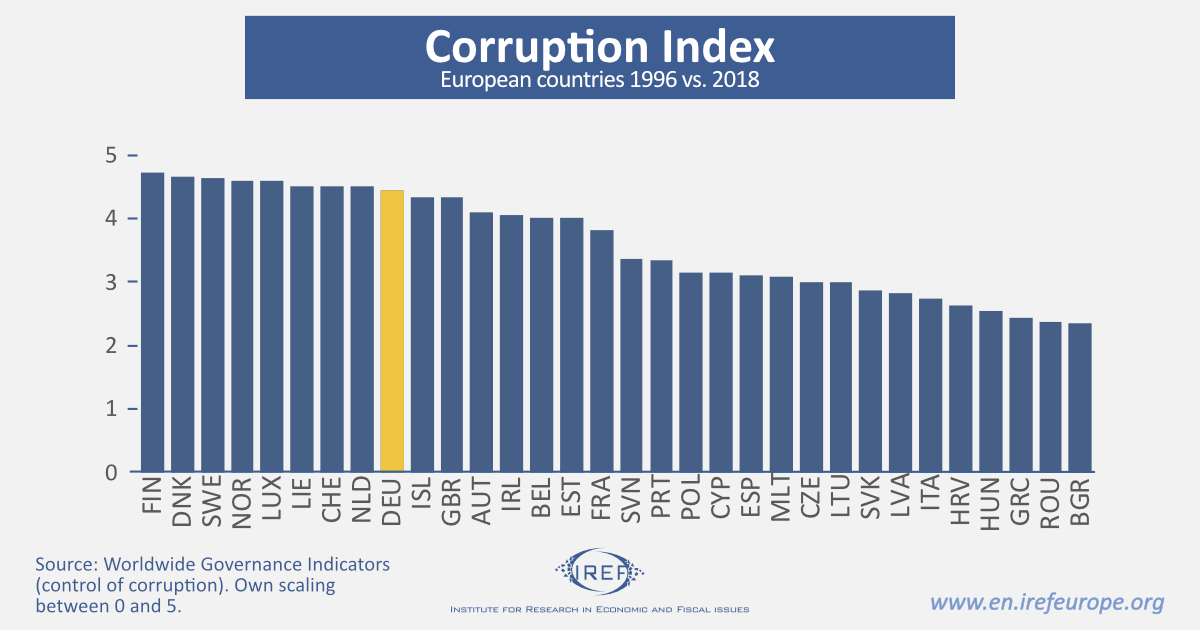

The World Bank data on “control of corruption” and governance assessment reveals how corruption within the public sector is perceived in various countries. The World Bank analyses the answers from by citizens, companies, and experts and collected by surveys conducted by pollsters, think tanks, NGOs, and international organisations since 1996 for over 200 countries. The outcome is a corruption index, which shows that corruption within the EU and other Western European countries is perceived to be the lowest in Finland and the highest in Bulgaria.

All Scandinavian countries do particularly well. Public sector corruption is seen as particularly common, however, in some Eastern European countries as well as in Spain, Greece, and Italy.

1996 vs 2018: Disillusioning development in Hungary

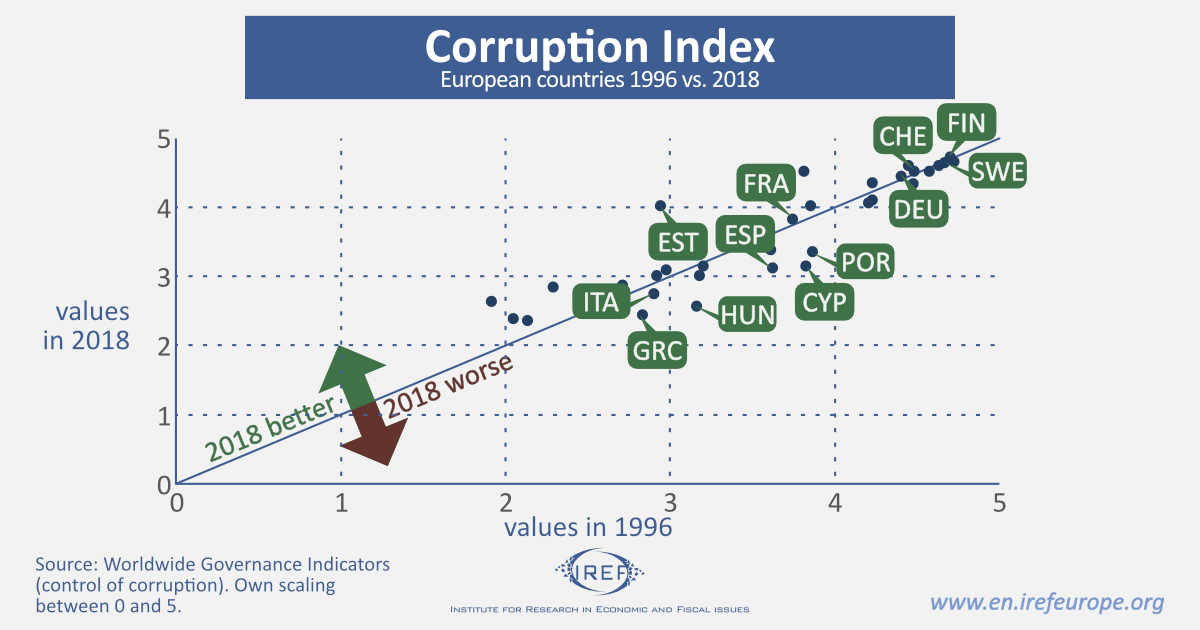

The data from 1996 and 2018 show that the extent of corruption is persistent. Nonetheless, changes are possible: although a high degree of corruption is not inevitable, a low degree of corruption likewise does not prevent the situation from getting worse.

Since 1996, Estonia has experienced the strongest positive changes. By contrast, in Cyprus and Hungary the developments have been disappointing, as well as in Portugal and Spain. In Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Germany, and France, almost no changes are registered.

Corruption leads to wastages

When it regards the governmental sector, corruption means that civil servants abuse their positions for their own private benefit. This does not necessarily correspond to illegal behaviour.

There is plenty of empirical evidence of negative consequences, for example with regard to investments, international trade, the brain drain, budget stability, and education. Corrupt structures also cause harm by making the productive use of real resources less attractive. If corruption is widespread, people have weaker incentives to engage in production and less time to innovate, invest, or improve their education and skills. In brief, being productive does not pay – or pays less – when civil servants appropriate at least part of the fruits of someone’s labour. At the same time, high corruption encourages people to devote resources and time to unproductive activities, and strive to acquire privileges by interacting with corrupt officials.

Success in Estonia

This explains why the data mentioned above suggest that corruption is more or less stable across countries and over time. When corruption is low, the productive use of resources is particularly valuable, while unproductive uses are less promising. The opposite is true in a country where corruption is high. The conditions of beneficial or harmful equilibria contribute to their own maintenance.

Yet, some societies manage to break out of rigid corruption systems. In the 1990s many countries established independent anti-corruption authorities. Latvia and Lithuania did so to comply with requirements to join the European Union. However, Estonia did not. In fact, the Estonians preferred to rely on the existing authorities, under the direction of the ministry of the interior.

According to data by the Heritage Foundation, Estonia is one of the 10 most economically free countries in the world. The absence of excessively complex regulation reduces the possibilities for corruption. Another factor that is likely to contribute to the fall in corruption could be Estonia’s extensive e-government. For example, if applications are filed and handled electronically, it is harder for civil servants to manipulate their outcomes to their own advantage. Additionally, the low amount of corruption and the associated measures taken in the 2000s are to be traced back to pressure exercised by public opinion, who were no longer willing to tolerate high levels of corruption. If a large number of people stops seeing corruption as legitimate, political decision-makers are encouraged to react, and make sure that the anti-corruption measures are more effective.

Of course, there is no guaranteed recipe to fight and eliminate corruption. Nevertheless, recent developments in countries like Estonia justify cautious optimism. In particular, they show that corruption can be tackled successfully if citizens, organisations, and political representatives take the initiative and strike back.