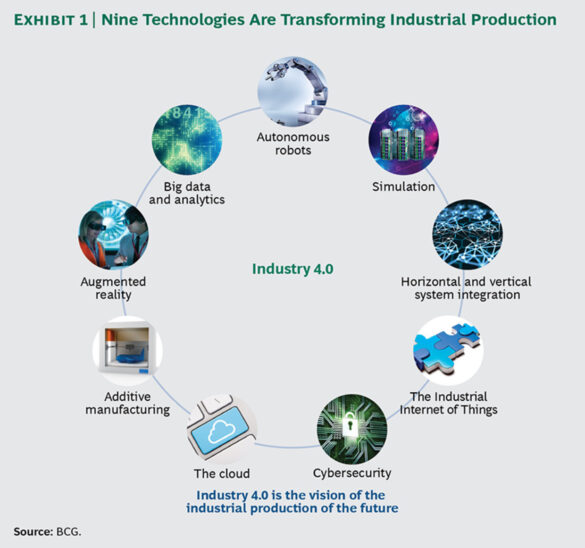

In the last few years, the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) has become one of the most investigated and discussed topics in the political and economic debate. 4IR is based on the application of new technologies, primarily digital ones, in production. Specifically, according to Boston Consulting Group, nine “enabling technologies” are crucial for the birth of the “smart factory”, a highly innovative and technologically advanced method of production.

However, despite its promises, 4IR also arouses worries, especially for its impact on employment. Some researches forecast the “end of the job” in a near future. Others are less pessimistic in terms of job losses, but all analyses have stressed that radical changes are imminent; some jobs will almost totally disappear, and we still cannot forecast properly the jobs of the future.

Certainly, we should brace for major changes in the entire social structure.

In particular, two aspects of the 4IR deserve attention. First, 4IR affects the whole cycle of value production and therefore concerns services, distribution, logistics, and interactions with consumers. It has an enormous impact on how goods and services are acquired and used, and also on how individual preferences (through the big data analysis) will influence the world of business and production. A confirmation, in a new and more decisive way, of “consumer sovereignty”.

The second aspect is that, unlike other economic revolutions, it is not based on a single invention, or on a well-identifiable group of inventions, but on an incessant flow of inventions. They are generated everywhere in the world and, thanks to the internet’s ability to break down physical and temporal distances, they can emerge in contexts that are very different and far from those in which they were produced. The main characteristic of this revolution is the interconnection of machines in the production process, as well as the interconnection with consumers, suppliers, and technological and economic partners. In brief, it is the capacity to be interconnected with the incessant flow of inventions and data.

Therefore, 4IR is also a cultural revolution, one that must be understood in terms of the theory of knowledge. It requires that we are equipped with new technologies and a new mentality; and ready to bring about changes in the traditional business models of the firms. The revolution is, therefore, more in the way of using new technologies than in the technologies themselves; it is a revolution in the way knowledge is used.

The main problem of economic life is how to use most efficiently a body of knowledge that cannot be owned by anyone in its totality and cannot be centralised by any authority. This very problem is crucial when we analyse the incessant flow of innovations that characterises 4IR. In fact, Open Innovation is the paradigm for understanding 4IR: a paradigm that encourages companies to achieve innovation by becoming permeable to the stimuli that come from very different actors and contexts. Innovation is not just what is produced in a firm’s laboratory, commissioned in research centres, or achieved by imitation of competitors. The innovation that can generate greater value is often the original application of something that has been conceived and invented in another context and for other purposes, a phenomenon already observed in the past but one that will be much more diffuse and persistent.

Massive investment plans have been put in place by several governments to promote 4IR – both in mature economies, which hope to attract new manufacturing capacity, and in newly developed countries, which do not want to lose their recently acquired competitiveness. These plans follow very different approaches. Some (e.g., “Made in China 2025” but also “Industrie du Future” in France) give priority to public spending and to the public guidance of private investment. Some (e.g., “Impresa 4.0” in Italy) implement public spending, but leave the private sector free to decide how to use the resources available. Others (i.e. “Manufacturing USA”) promote a mixed approach, creating networks composed (and financed) by big private companies and universities or other public research bodies.

The dominant model is the public-private partnership, and a popular idea, rooted above all in continental Europe, is that 4IR cannot be obtained without the decisive contribution of the state, which should produce the necessary “4.0 infrastructures” (e.g. the Internet broadband), develop suitable norms and standards, and grant tax incentives. Of course, the idea that the state has to provide the infrastructures and the incentives for Industry 4.0 is consistent with the statist idea that market operators should be directed towards what is best for them, rather than leaving them free to make their choices and to correct their mistakes. Yet, one can predict that bureaucratic paternalism and subsidises entrepreneurship will be part of the problem, rather than of the solution. Abandoning the quest for privileges could be even more daunting than meeting the 4IR challenge.