Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Uber, Airbnb: these are only few of the numerous companies which have fundamentally changed our lives with new technologies in recent years. While their business models differ, none of the stars come from Europe. Apart from the serial entrepreneurs at Rocket Internet in Berlin, SAP is the only big digital corporation in Germany. Is there a role to play for the EU in the attempts to change this? Yes, there is. However, not by means of new subsidies and detailed regulation, but by keeping markets open.

Few tech companies in Europe

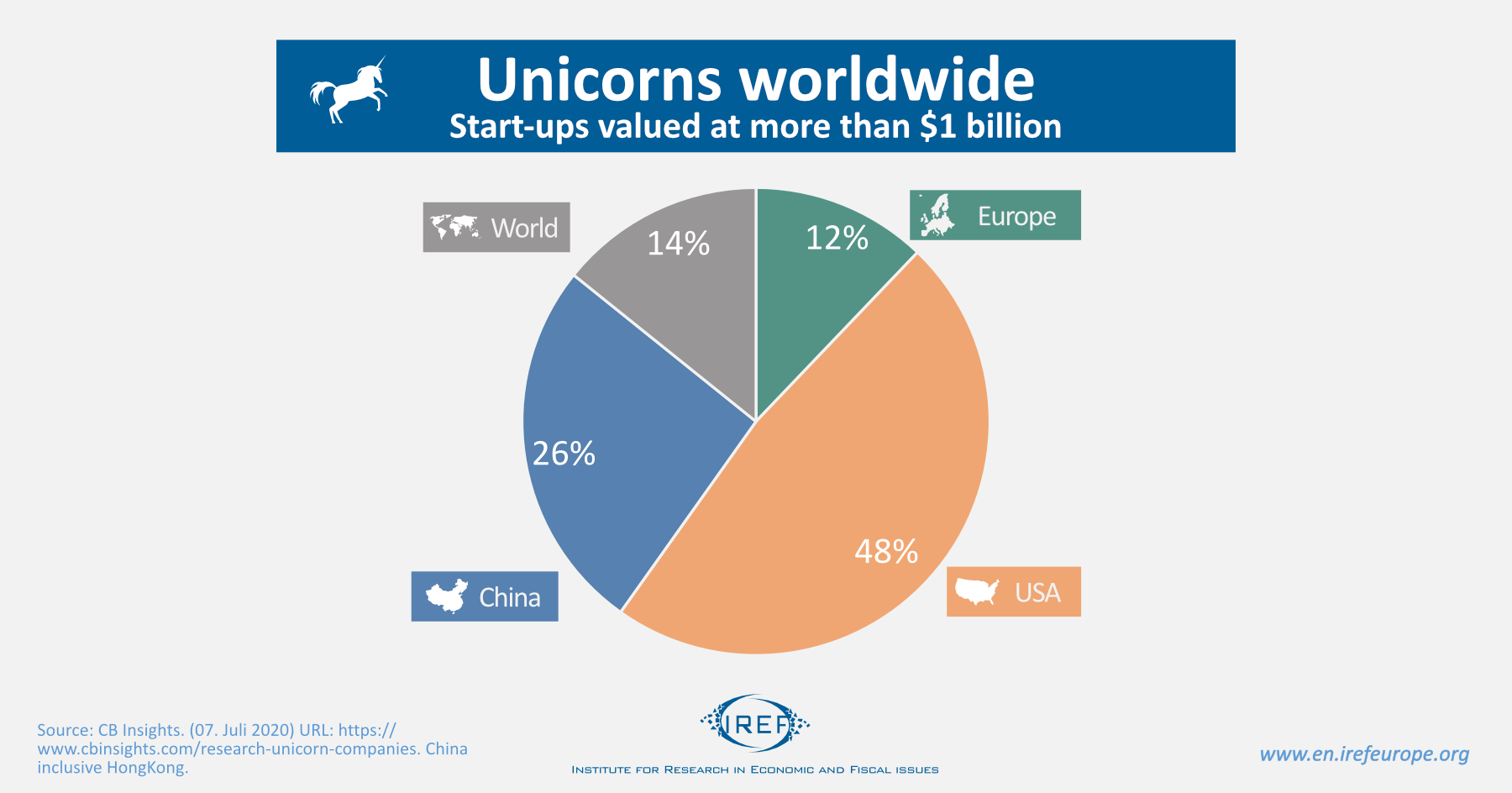

Europe looks rather bad not only with regard to the established top dogs, but also when it comes to the potential superstars of the future. An up-to-date overview of start-ups which are or will soon be valued at over $1 billion can be found at CB Insights, where almost 480 start-ups are currently listed. They are usually IT-centred and often specialised in software. Almost half of them come from the US. Roughly a quarter is based in China, only about 12 percent in Europe – of that, 40 percent are British.

A number of factors are to blame for the absence of globally leading European tech companies. Many of them cannot be controlled by the EU.

Euro-Valleys are missing

In Europe, there is a painful lack of clusters in which knowledge-based enterprises are tightly connected with leading research institutions. While leading universities such as Stanford and Berkeley send talents to innovative companies in Silicon Valley, Europe lacks top level research institutions, particularly on the continent. There are only two continental European universities among the global top 20, both of which are Swiss.

Promoting clusters is, however, not one of the EU’s tasks. Firstly, clusters are inevitably regional. For instance, Spain would have little interest in co-financing a research institution in Eastern France. Secondly, education policy is made on a national or, like in Germany, on a regional level. Consequently, individual member states and their local administrative units are responsible for laying the foundations for successful research at universities, research facilities and individual companies – regardless of national borders.

Little venture capital

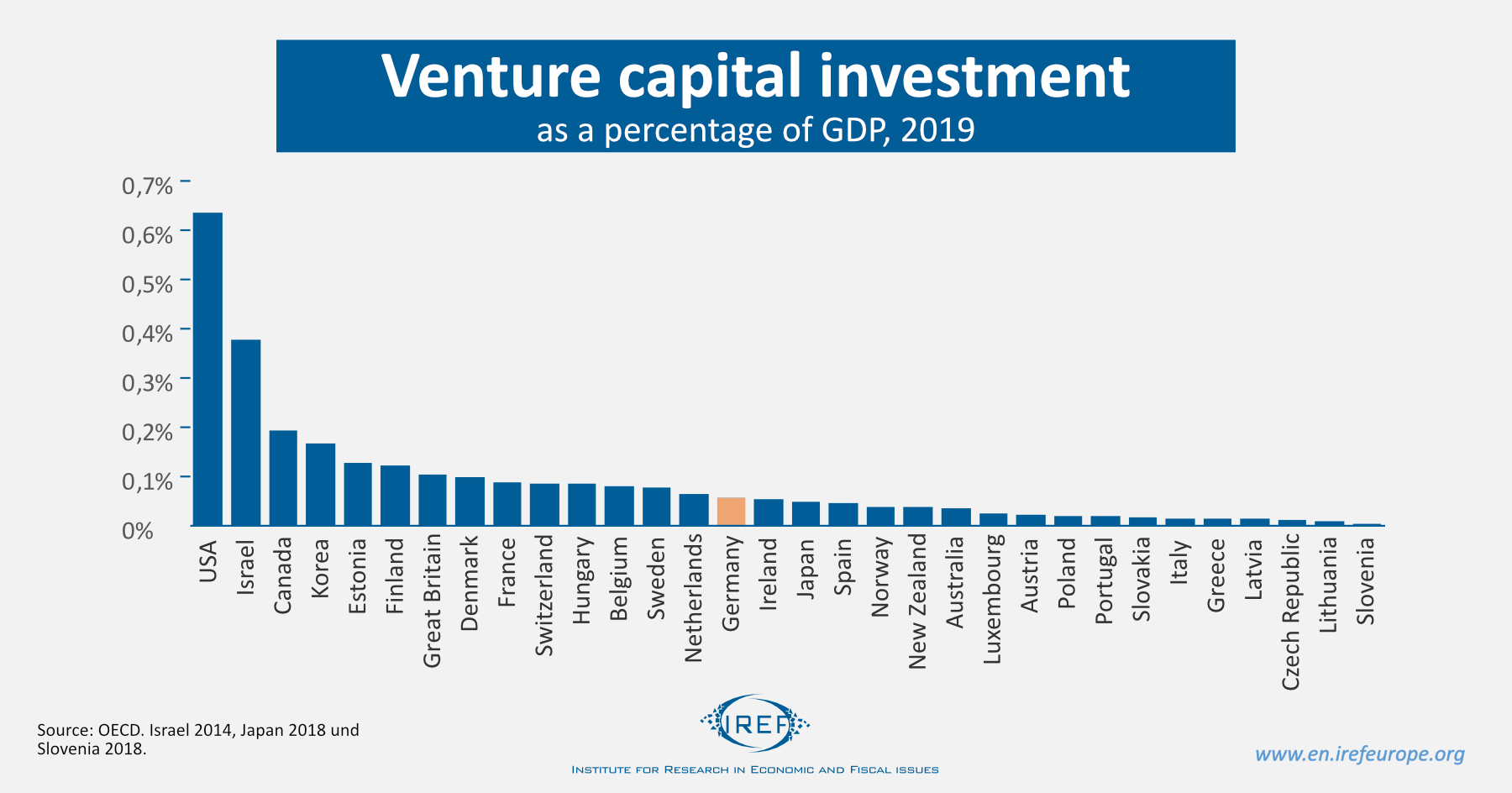

Young firms aiming to implement risky business ideas often resort to venture capital providers instead of bank loans. According to OECD data, European countries lag behind the US in this domain, too. In 2019, the amount of venture capital provided in the US was as high as 0.63 percent of GDP. In Germany, it was around 0.056 percent, a tenth of the US portion.

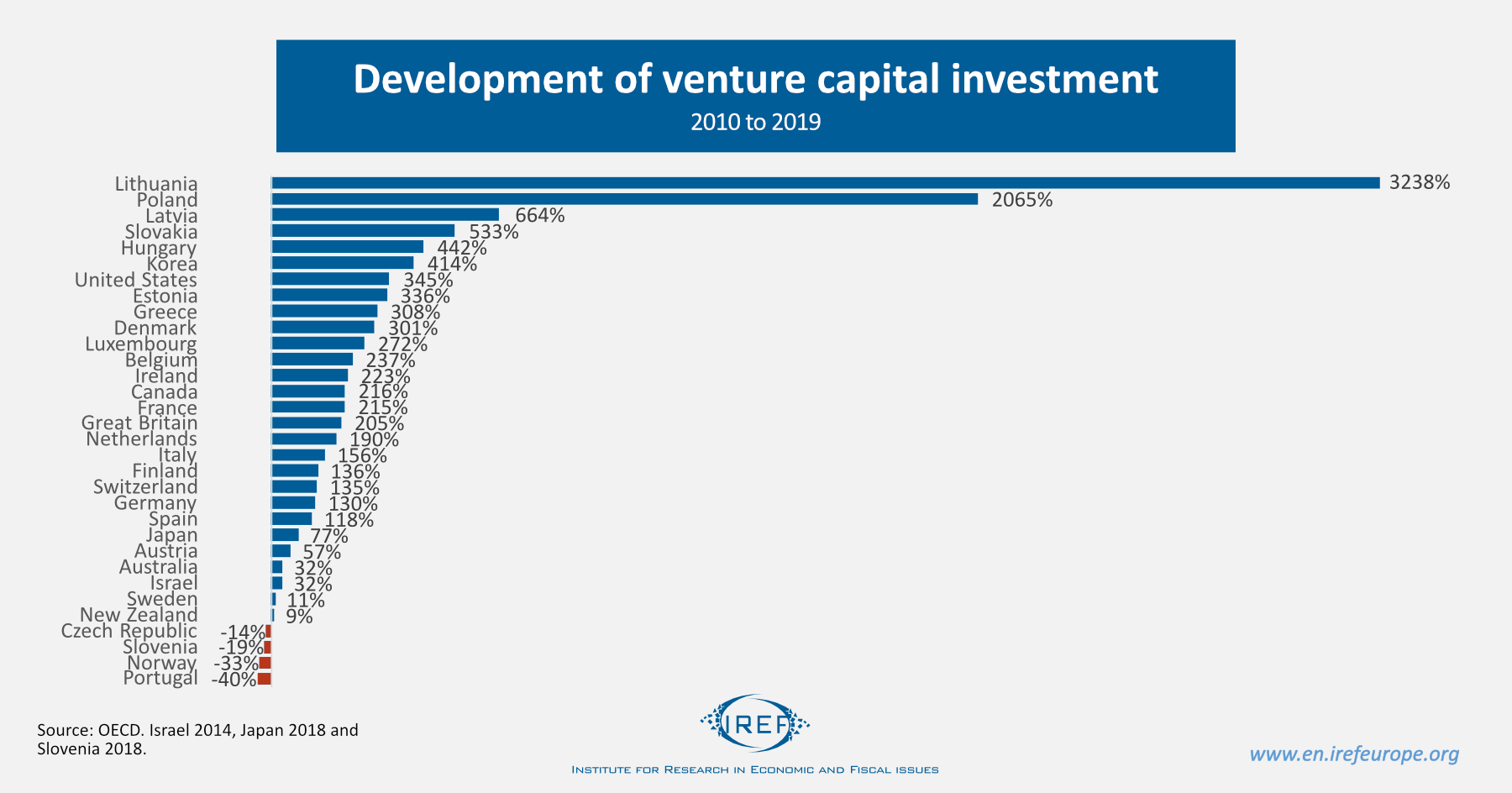

The gap between the US and Germany with regard to venture capital has not decrease in recent years. In fact, the opposite happened. Between 2010 and 2019, the volume of venture capital increased by 345 percent in the US, 215 percent in France, and 130 percent in Germany. Some Eastern European countries as well as Korea exhibited a higher relative gain in venture capital compared to the US. All other EU countries experienced lower growth rates or even a decrease.

Venture capital and innovative business ideas go hand in hand. In the US, networks of research facilities, companies, successful entrepreneurs, and investors have developed in California but also on the East Coast around Harvard University and the MIT. Such networks cannot be built according to plans and decisions. The EU should consequently not attempt to promote Europe as a technology hub through direct funding, e.g., via the European Investment Bank. The EU does not have the necessary expert knowledge and its representatives do not face the same incentives as private investors. Since private investors are using their own means, their actions are determined by risk-taking entrepreneurial insights and careful investigation. The mere provision of venture capital does not lead to good business ideas.

Bigger economy, smaller markets

If successful new companies in the IT industry begin to grow in their domestic markets, having a bigger domestic market is an advantage. The European Single Market is huge, even compared with the US, since in encompasses around 500 million consumers. But the market remains fragmented. One reason is the presence of linguistic and cultural barriers. The EU has 24 official languages. Providers have to translate contracts, terms and conditions, websites, and apps 23 times if they want to serve the entire EU market. This condition can hardly be changed by political decisions. Additionally, legal and regulatory specifics on the national level make it harder for firms to serve the EU market from the beginning and thereby to reach a globally relevant size.

While the European Single Market for goods is largely free from national barriers, this is not true for services. This is where the EU has the most potential to generate better preconditions for European start-ups.

The digital single market: liberalising services

There are two instruments to get rid of legal and regulatory hurdles for cross-border trade of goods and services.

First, rules can be harmonised. The digital single market strategy from 2015 aims to further match contract law regulations for online businesses. Traders then have fewer national specifics to consider and consumers can trust domestic and foreign suppliers to be guided by the same rules. Regulatory harmonisation, however, comes with the danger of hindering possibilities to experiment throughout the entire EU. Second, regulations could be mutually recognised. This alternative allows an easier exchange of goods and services without the potentially harmful consequences of harmonisation. This is already common practice for goods for which there is no uniform EU legislation. Commodities which enter the market legally in one member country may also be sold in other EU states. The principle of mutual recognition is not applied to services yet, even though the European Commission had intended to do so.

The draft for the directive on services in 2006 planned that the country of origin principle should also apply to services. This would have led to legal services from one country being legal in other EU states, too. Instead of following the principle, rules for services were harmonised – with extensive exceptions. There are no harmonised rules for services of “general interest”, financial services, services of electronic communication, public and private health care services, transport services, and gambling. These areas remain under national control. The exceptions show that the European Single Market is fragmented precisely in those industries which are particularly promising for digital innovations.

In order to enable European providers of technological services to access a truly joint domestic market, the EU should switch to mutual recognition of rules concerning services.

Getting rid of barriers

Although the EU’s possibilities for promoting a European digital hub are limited, they must not be neglected. The EU should not try to actively build regional clusters for the digital economy; it should not attempt to operate as venture capital provider, either. Instead, it should focus on one of its core capabilities – unifying the single market by opening up national markets. This would assist digital business ideas, which are often guided by network effects; and start-ups in Europe, which could eventually lead to global success.