The term meritocracy describes a social and political context in which merit is the key criterion to evaluate the distribution of rewards. If such distribution reflects individual merit, it is fair. It is unfair in the opposite case. The term was coined in 1958 by British sociologist Michael Young, according to whom meritocracy describes a dystopia, not something necessarily desirable. Young was affiliated to the labor party. In fact, the term maintained a negative connotation for a long time within the leftist culture. Since the 90s of the last century, however, the world of politics took at different view, possibly encouraged by egalitarian theories that sought to combine egalitarianism and personal responsibilities.

Tony Blair and Bill Clinton were the champions of this new approach. Barack Obama was another strong advocate of the idea that rewards must follow merit. Hillary Clinton also belonged to this camp, although her loss to Donald Trump showed that a large part of the American electorate felt uneasy about this term. The reason was simple: rather than describing an ideal society, the term ended up justifying the status quo, and triggering bad feelings among many Americans, especially those whose economic conditions and social status had been declining in the previous two decades.

According to The Tyranny of Merit, a recent book by Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel, resentment against meritocracy was reinforced by the morally unattractive attitudes that the meritocratic ethic promotes. It generates hubris among the winners, while it unleashes humiliation among the losers. According to Sandel, these reactions are at the heart of the populist uprising against the elites. Indeed, the populist unease about the tyranny of merit would prevail upon hostility towards immigration and delocalisation.

Middle classes and social mobility

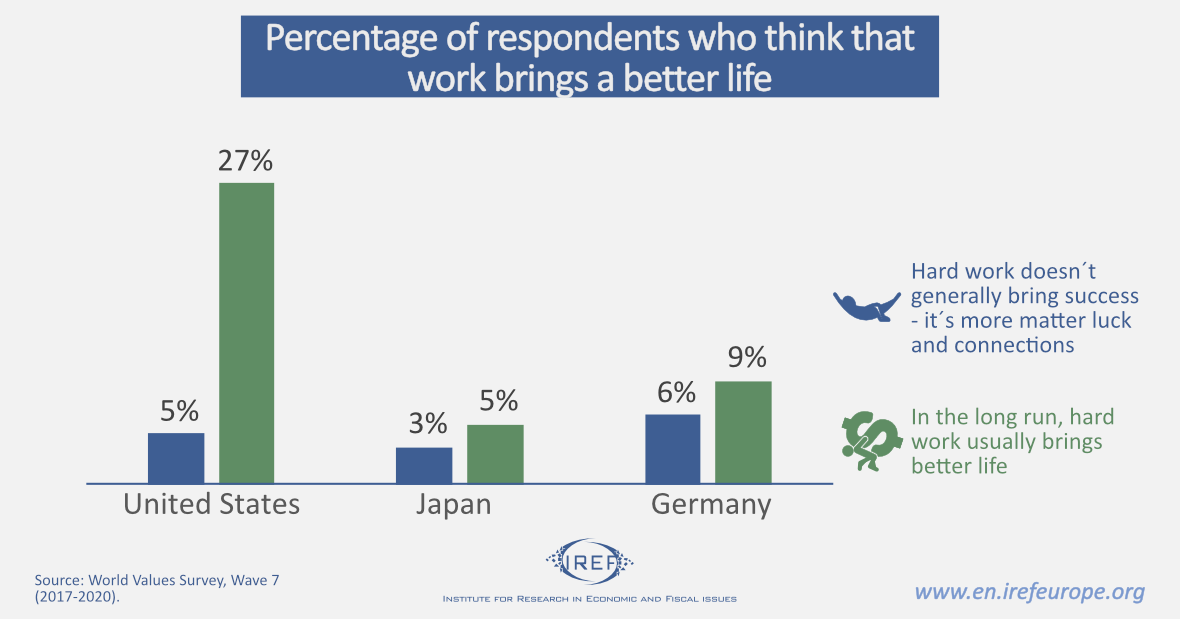

Americans typically trust that hard work brings success. By contrast, surveys show that Germans and Japanese are far less persuaded by this narrative.

The American view has consequences. If those who work hard have a good chance to succeed, then those who fall short have no one to blame but themselves. Thus, social positions reflect what people deserve. In this perspective, equality of opportunity corresponds to offering a chance to rise to all individuals, regardless of their starting points. Put differently, social mobility becomes the answer to inequality. However, by the time Hillary Clinton ran for presidency, the impoverished middle classes no longer accepted social mobility as the solution to their problems. The populist upheavals of 2016 — the election of Trump in the United States — was perhaps a successful attempt to repudiate “meritocratic” elites.

Meritocracy and its caricatures

The meritocratic standpoint sees the assignment of individuals to places in the social hierarchy as the result of a process in which all the members of society are competing agents. Sandel himself recognizes that merit is a fair a criterion to obtain distributive justice. Consequently, the very title of his book is perhaps misleading, since Sandel actually is not against the meritocratic ideal per se, but rather against its caricature.

This is clear if one examines one of his proposals to reform access to tertiary education. As he argues, colleges and universities preside over the system through which modern societies allocate opportunities. However, there is evidence that many American universities accord priority to the children of alumni and generous donors (these circumstances often coincide). Sandel argues that this is unfair, and suggests that access to the elite colleges should ignore legacies and consider merit with prudence: “Even the wisest admissions officers cannot assess, with exquisite precision, which eighteen-year-olds will wind up making the most truly outstanding contributions, academic or otherwise”. In his view, admissions should be based on selecting a relatively large set of candidates that meet given standards, and then picking the winners by lottery. This proposal clearly does not ignore merit, since only those qualified are admitted. Yet, it treats merit as a threshold, not as an ideal to be maximized, and avoids humiliating those who fail.

To repeat, Sandel’s book is not against meritocracy. Yet, it raises some questions. In the Middle Ages, people were inclined to accept the distribution of the social order as a result of God’s will. Today, the meritocratic rhetoric suggests that Western societies actually follow standards dictated by talent and distinction, and ignores that in the real world the distribution of power is also characterised by the self-perpetuation of privileges. Indeed, when a community flaunts meritocracy and actually tolerates practices that are not based on its founding principle, then individuals move away from meritocracy and devote resources to acquiring privileges. The upshot is that the previous social hierarchy based on caste systems risks to morph into one based on pseudo-meritocratic order in which privileges continue to prevail and dissatisfaction remains extensive.