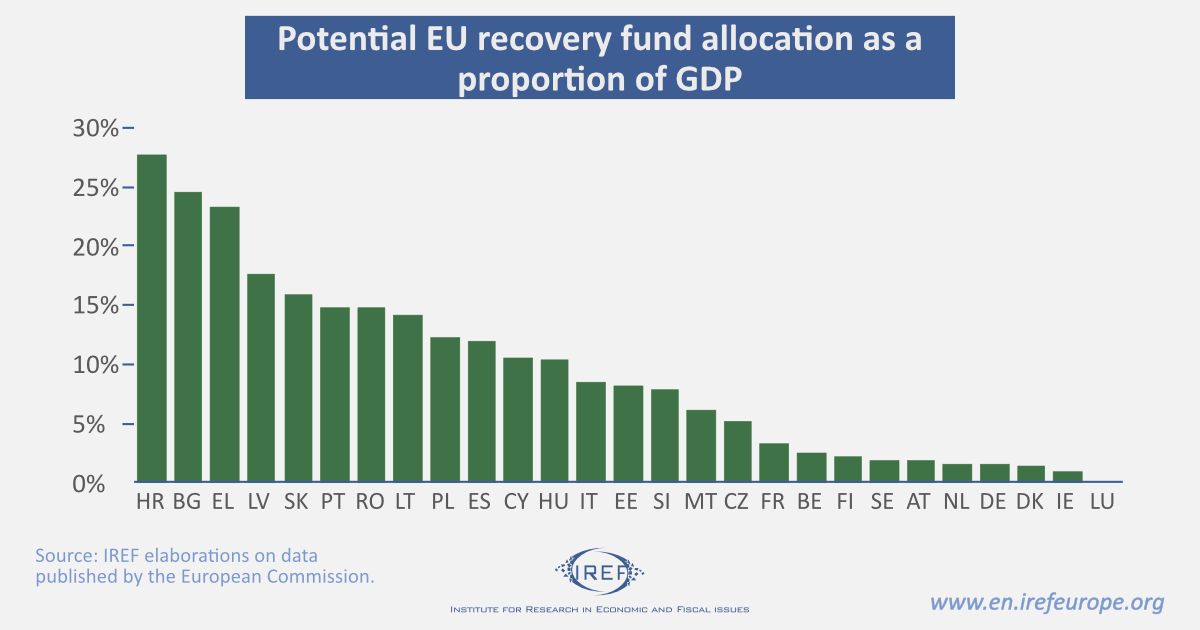

After many days of fierce bargaining, the EU political leaders have eventually achieved an agreement about the magnitude of the stimulus package deemed necessary to restore sound conditions for the European economy. The deal was expected. A fiasco would have badly shaken financial markets (with consequences) and raised further doubts about the ability of the current political establishment to steer the ship through stormy seas. The € 750 billion recovery package to soften the Covid-19 crisis will be particularly welcome by the Eastern and Southern European countries, as emphasized by the European Commission in its Staff Working Document, Identifying Europe’s recovery needs . Besides, it has also been agreed to widen the 2021-2027 EU budget, up to € 1,074 billion. In other words, the EU’s next seven year budget and the Next Generation EU programme (the so-called recovery plan) will provide a total package of € 1,824 billion.

The big news is that the Commission will be able to borrow up to € 750 billion on financial markets. Although these funds will be repaid by 2058, the source of the resources is not entirely clear. One possibility is to reduce future EU expenditures and run a budget surplus. Another is to obtain the same result by increasing taxation. In this respect, a new EU plastic tax will be introduced in 2021. Next year, the Commission is also expected to put forward a proposal for a carbon adjustment measure and a digital levy, to be introduced by the end of 2022. Additional resources might be also collected through a financial transaction tax.

However, new taxes will be introduced only if the member states agree. This is by no means guaranteed, since some members are reluctant to give the Commission autonomous taxing power. And it is unlikely that EU expenditures will go down in the next years. Thus, the Next Generation programme raises an important question: who will repay the debt?

News from Brussels

Empowering the Commission to borrow from capital markets on behalf of the European Union is the most important novelty introduced by the deal. These funds will flow to the EU budget as an external assignment and will be used to finance the recovery. It was at the end agreed that € 390 billion will be distributed as grants to member states, whereas € 360 will be given as loans. The grant component was sensibly reduced from the € 500 billion previously recommended by the Commission, following opposition from the so-called Frugal Four (Denmark, Sweden, Austria and Netherlands), who firmly asked to cut the loan component and recommended a more balanced mix. However, and with an eye to saving the euro and intra-EU free trade, the core EU countries have agreed to a mechanism that assigns a large share of the benefits to the peripheral countries.

After acute tensions between Italy and the Netherlands, a spurious form of conditionality was agreed. Member states will prepare national recovery and resilience plans for 2021-2023. These will be consistent with country-specific recommendations, focus on boosting growth, employment, and reinforcing the economic and social strength of the EU bloc. They will be approved by the Council by a qualified majority vote on a proposal by the Commission. Grants will be provided only after the Council’s consent. However, any member state can (temporarily) stop disbursements to any country in case of presumed violation of the commitments described in the plans. The Commission will be the ultimate judge. Overall, the fierce bargaining about the size of the package and its allocation and the introduction of veto power for each member country also showed that the European Union is definitely not a federal state, and that its decision-making process is slow and cumbersome.

Winners and Losers.

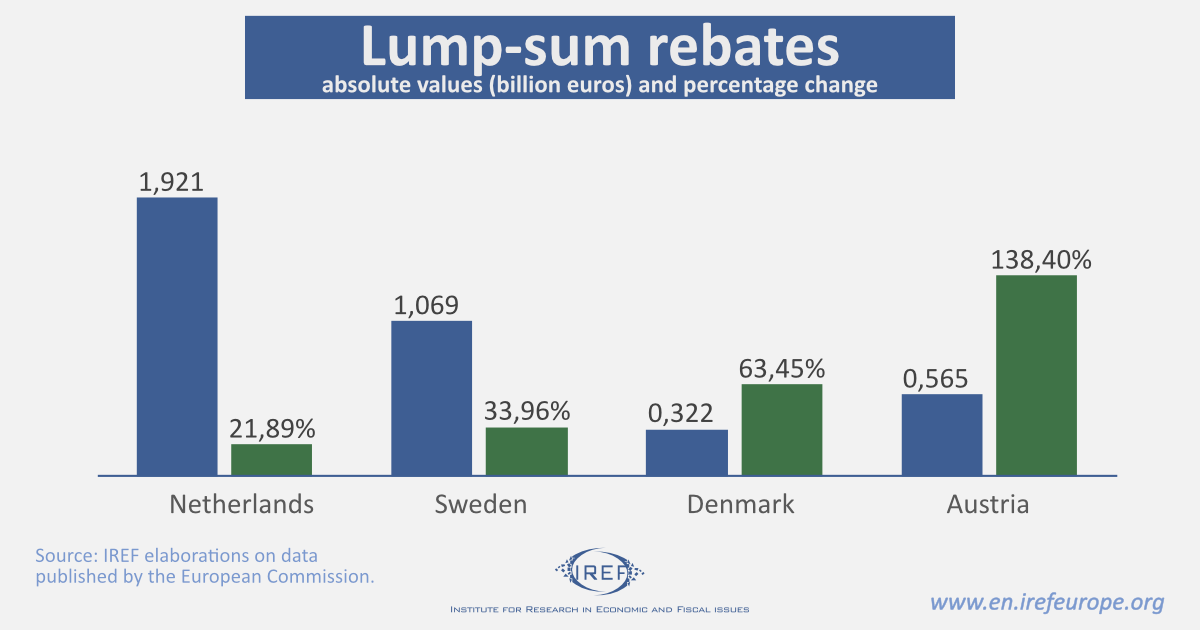

As it is always the case when politicians have their reputation at stake – general elections are the obvious example – they all claimed they got exactly what they were demanding. President of the European Council Charles Michel was clearly very happy with the deal. Although not exactly enthused, Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte claimed credit for the introduction of a procedure that freezes disbursements to governments that do not fulfil their promises. Some are not persuaded, though: Rutte is currently facing strong dissent at home and a referendum about some kind of Tulipexit is not pure fantasy. Nobody, on the other hand, had imagined that the Netherlands, with a population equal to about 7% of the population of the big four (France, Germany, Italy and Spain) could have been such a tough nut to crack. Obviously, Rutte knew this since the beginning. His strategy was primarily aimed at describing the south European countries as slack and irresponsible, and at trying to get the best out of the deal in terms of resources. Indeed, lump sum rebates on the annual GDP-based contribution will be increased for the Frugal Four, with the Netherlands getting the lion’s share in absolute terms (1.92 billion, against annual refund of 377 and 565 million for Denmark and Austria respectively).

On the other hand, Giuseppe Conte and Pedro Sanchez have good reasons to celebrate. These EU funds should allow them to weaken populist pressure and, more generally, strengthen their political position at home. Yet, the future for them will not be easy. Southern countries must show their capacity to use the resources at their disposal to stimulate growth and employment and make their economies resilient to future shocks. This is probably their last chance to stay in the EU as we know it.