The impression from media is that companies pay “only” somewhere around 20-30% tax rate in the EU, if they pay at all. That’s only the headline figure for one tax they pay. Total tax rates are well over 40%, French businesses pay 2/3 of their profits in tax. What’s worse, the big economies of Germany and France, already heavy taxers, have increased the tax rate over the past 10 years. This does not bode well for the future.

The European Commission likes to fight “unfairly high prices”; mobile roaming charges are a recent example. Yet when it comes to price of government services, it takes the opposite approach. In the “LuxLeaks” campaign it wants ultimately to unify corporate tax rates at the high end of their European spectrum. Some countries’ low rates of corporate income tax is seen as “cheating” against “proper” (read: high) rates. Only last week commissioner Moscovici said that “the Commission feels it’s time to establish fiscal equity, so that companies pay what they owe”.

Commission’s concentration on corporate income tax rates distorts the picture of corporate taxation. Companies pay all sorts of other taxes (at different rates). When making their business plans (including choice of location), companies have to consider the country’s whole package of taxes it will have to pay, not just the corporate income tax.

What various taxes are companies paying?

• Corporate income tax. This tends to be the only tax discussed in most popular debates. Generally it is set as a percentage of profits the company makes over the fiscal year. Even if the rate is harmonized one day, as the Commission wants, there will likely remain great national differences in accounting rules, what counts as eligible costs (lowering the profit), and indeed what revenue is relevant.

• Labour taxes. Companies have to pay in tax not only a percentage of wages paid to their employees (this is in addition to personal income tax deducted from the employees’ gross wages), but also a further percentage to social (and health) contributions. Governments sometimes like to pretend that they are making companies contribute to the workers’ welfare by this scheme, especially when these taxes are paid to a private fund chosen by the worker.

• Property taxes. Companies have to pay property taxes just like natural persons, sometimes even at a higher rate. In addition, there is also an implicit property tax resulting from governments’ zoning regulations. Business is allowed only in designated properties, whose artificial scarcity increases their price.

• Turnover taxes. These usually take the form of a value-added tax in the EU, but also include import duties and others. The EU has already made big advances in harmonizing the rules, although the rates are still allowed to be set by national governments.

• Other taxes. The list of other taxes on companies is very rich, governments seem very inventive. Vehicle taxes seem quite popular, for example. Even countries which do not impose a vehicle tax on privately owned cars generally do impose it on company cars. Licensing fees are also popular, which limit access to the market and reduce competition. Various municipal fees tend also to be standard fare in most countries. The list seems endless.

Companies are not only tax payers but also tax administrators for governments , collecting taxes from some other payers (e.g. withholding). These are not included in the overview above, although they do add to the admin costs.

How much tax are EU companies actually paying?

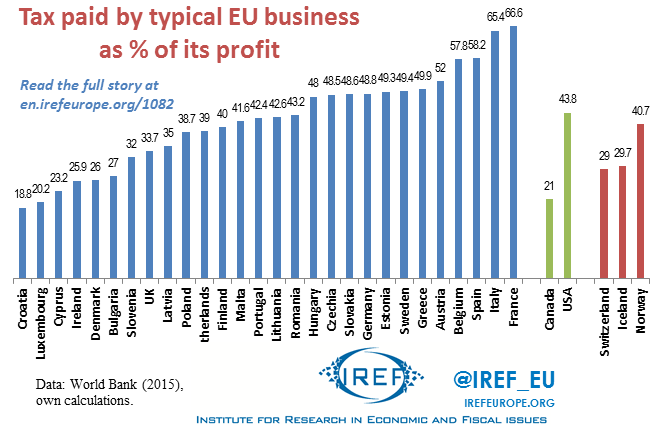

When the Commission wants to talk about “corporate tax competition”, it should consider the whole above package of taxes, not just the headline figure of the corporate income tax. Of course, this multi-factor comparison is difficult because of the large differences in small-print across individual member states. Helpfully, there is a solution. The World Bank uses an example of a standard medium-sized company across the world and calculates how much such company would pay in its second year of business in taxes, as a percentage of its typical profit.

The data therefore provide a more complete picture of the true cost of doing business in a country, considering the effective and not the headline tax rate, of all the five main groups of aforementioned taxes and not just the first. The latest 2015 report offers this picture:

It perhaps comes as no surprise to see the usual suspects in the high-tax group: France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Sweden… But the actual effective tax rates should give us pause. Five EU countries tax away more than half of their typical companies‘ profits, and a full dozen countries tax 48% or more. Even the average rate is very high at 42%. At the low-tax end, Croatia surprisingly beats Luxembourg, although the fear is that after more time in the EU, it will “learn” from other member states what more can be taxed; the Croatian budget is pretty tight.

What changed over the last 10 years?

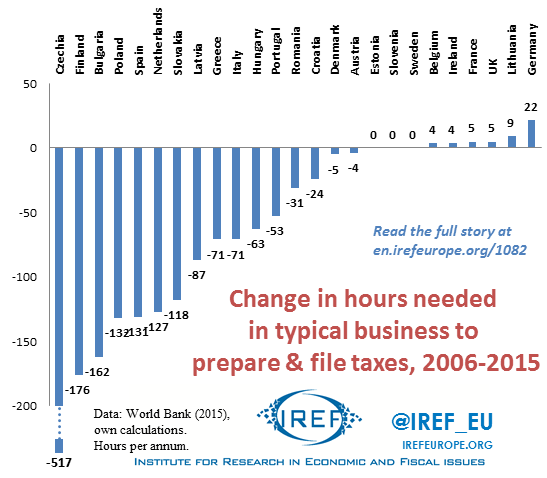

These high tax rates suggest that the “race to the bottom” (invoked to justify tax harmonisation) isn’t much of a race. But let’s consider the data. This year’s report is the tenth in which tax rates have been calculated (for nearly all current members) so we can consider the development over the last decade.

At first blush, the overall results show that although the tax rates are high, at least they are coming down, even in large economies such as Italy. The overall rate is very slow though – median rate of 0.3 percentage point per year is hardly helping the EU in its 2020 vision of improved “global competitiveness”. Most worrying, however, is the fact that three countries actually impose a higher tax rate on their companies’ profits than ten years ago.

France and Germany are the rotten eggs

Ireland may perhaps be “excused”. Recession hit it hard and its rates remain among the lowest. However, that Germany and France have increased their taxes is a pretty disastrous finding because they already belonged to the highest taxing countries.

In light of this, we could conclude that instead of a “race to the bottom” we are seeing hints of a “race apart”, where high taxation is often increased further. There is another way of showing that “something strange” is going on in France and Germany: We reported recently the latest figures on the length of time it takes to process and pay business taxes. Calculating the change over the decade we now find that both countries are among the 6 states where it now takes longer to do taxes. In Germany it went up by 22 hours, more than 10% increase!

What is happening in France and Germany has often dictated the future of the European continent. It is time for this trend to be broken, at least as far as trends in business taxation are concerned.