Desperate times call for desperate measures. European governments cannot raise enough tax to cover their spending. Ireland has even been forced to adopt what economists generally consider the least distortive tax feasible. That is good (considering the alternatives), but its execution leaves much to be desired. Strange incentives remain, and punishment for success is built in.

How PIGS became PIIGS

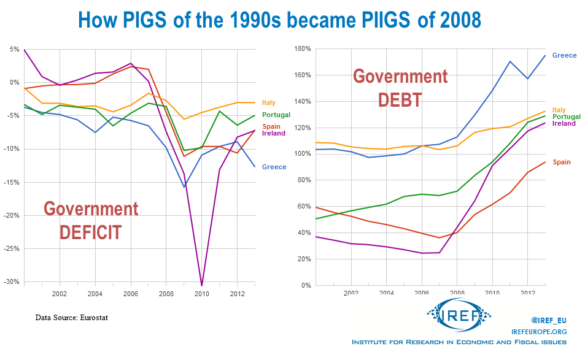

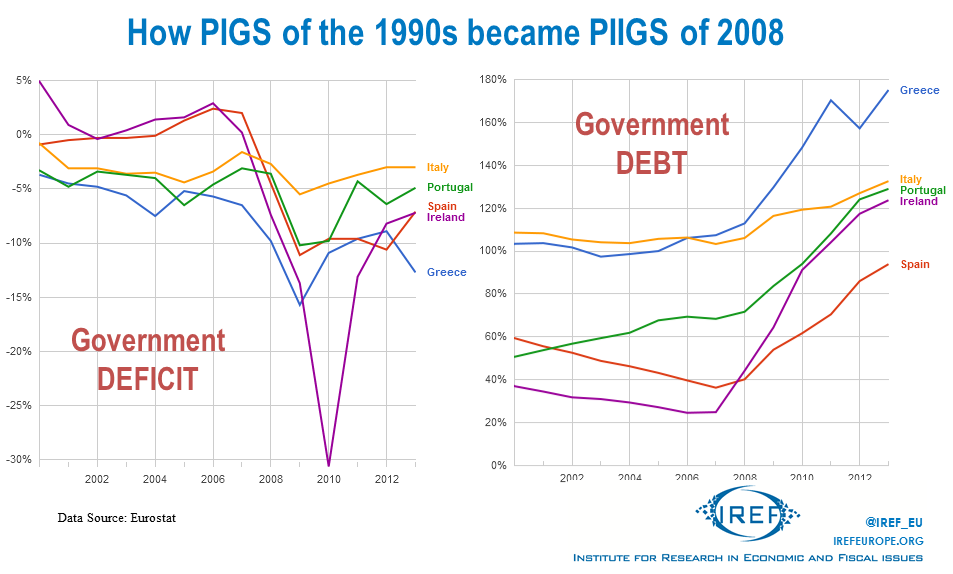

It is the 1990s. Most European economies are booming. Post-communist countries are finally seeing first fruits of transformation. Yet already there is talk about a group of economically weaker countries in the Mediterranean for whom the acronym PIGS was coined: Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain. The exact author is unknown, but the term was around already last century. It even had nothing to do with fiscal deficits – those were then associated with being STUPID: Spain, Turkey, UK, Portugal, Italy and Dubai.

PIGS were revived for post-2007 fiscal crisis, all of them experiencing a drastic rise of budget deficits. Spain, for example, went from a surplus (!) of 2% to a deficit of 11% in just two years (see graph). But even that was nothing compared to Ireland whose government spent an unimaginable amount of money bailing out the country’s banks. It went from a balanced budget (0.2% of GDP surplus) into a whopping 30.6% deficit, in only three years. And so PIGS morphed into PIIGS.

The Irish added in 2010 alone more to their debt than was its total accumulated size only three years earlier (at 24.9%). Fortunately, though, it was a one-off event and since 2012 Irish annual deficits are back at least in single-digit percentages.

Who pays?

Unlike other countries which are hoping their debts will simply go away (last week we reported on Spain actually cutting their taxes instead of cutting their spending), Ireland is trying to raise the money to pay off its creditors. The question is – what tax should it raise?

Ireland has rightly not touched its corporate tax rate which bore the Celtic Dragon. Ireland knows that corporations, being little more than a pile of papers filed somewhere in a registry, are extremely mobile and taxing them makes them go away.

Economists can actually calculate how much economic activity is displaced by taxing mobile targets. Historic examples of safe innocuous (“efficient”) taxation include tax on chimneys (it used to be difficult to live without one) or windows. But modern variety – the “community charge” – resulted in the downfall of the Iron Lady. As a result, no politician is likely to touch it again.

But there is a voter-friendly form of taxing without economic side-effects: property tax. Just like chimneys, property is difficult to move. We have recently analysed property taxes in OECD. Most countries tax property. But not Ireland. Until now…

Irish property tax

Introducing a new tax is never easy. To acclimatise the Irish to paying a property tax, the government first imposed a flat tax of €200 on any secondary homes (from 2009) and 2 years later also €100 on all principal residences.

There had actually been a brief spell between 1983 and 1997 of something resembling property tax, but it only applied to houses worth more than £100,000 and only as long as household income exceeded £30,000 (considerable sum then). It was more of a luxury tax with relatively few people liable. Owners could even avoid it altogether if they made a part of the building open to the public for at least one day.

Proper property tax starts now and is payable on every property. It is based on its assessed market value as of May 2013. For example, €90 is to be paid annually on all properties assessed at between 0 and €100,000. (After €1Million the rate rises slightly from 0.18% to 0.25%.)

Effects of property tax

As non-distortive as property tax may be, the Irish design does unfortunately create some secondary distortions.

The most obvious one was fortunately avoided. The assessed property value will fall into a “band” with pre-determined tax. Between €550,001 and €600,000, for example, the tax is set at 0.18% of the midpoint, i.e. €1,035, no matter what the valuation was. Since people tend to assess to round figures and these belong in Ireland into the lower, not the higher band. No more insincere incentive for silly valuations at €599,999 to save on tax.

However, banding itself seems quite unnecessary in an age of the digital calculator (let alone accounting software). Why create a table for people to read off the tax in their band when anyone can simply execute the “multiply by 0.0018” operation on even the simplest phone, watch or – perish the thought – paper and pencil? One-tax-for-whole-band discourages upgrading property currently valued near the upper band lest it falls into the higher tax bracket. A directly proportional tax would make the decision to invest into property upgrade quite independent.

One size does not fit all

An even more adverse effect of the current property tax system stems from its universality, the same rates being paid across all of Ireland. That cannot be good. If everything is set from above, the tax receiving local authority will have no incentive to behave efficiently. If anything, it will try to overestimate the valuations since that’s the only way it can currently extract more tax. People will not be able to vote with their feet for better local tax systems.

Better way is being able to vary the tax rate. In any economy, different geographic areas overheat and underperform. Labour should move to equilibrate, and different tax rates can aid in this process. European capitals are economically overheating and regions need to have something with which to attract, like lower tax.

Varying tax rates would also enable a better fit of services to tax-payers’ preferences. This works wonders in Sweden or Switzerland, for example, where people decide whether they want to live in a high-tax-high-public-services area or not. Arguments that income inequality is this perpetuated are not valid since local property tax does not fund the social security system.

Currently, the Irish face the same rates everywhere. This is set to change from 2015 when local authorities will be able to vary the central rate by 15%, but that is still too small a wiggle room. Fiscal competition needs no limits to benefit everyone.

Punishment for success

Ultimate spanner has been thrown into the works by central government. Fixed tax rate combined with greater property values have generated large tax rake in the four Dublin councils. Now the government wants to reduce their grants to offset the windfall.

This is bad policy. Firstly, the tax gains were easy to predict, so the whole system should have reckoned with them from the beginning and not hash out some quick-fix solution afterwards. Secondly, in a twist on the classic bureaucratic failure, this is a form of punishment for success. Every bureaucratic department fears being efficient – as the saved money is then just taken away from them.

Nobody says that local authorities have an automatic right to grants from the central government. Optimal policy would make local councils responsible for providing services within their budget, and vary their property and other tax rates accordingly, without resort to central funds. But this needs to be a universal policy, not an ad-hoc punishment for success.

If success is punished, people will create little success.