What is PEPP?

In March 2020, the ECB and European Commission announced the inception of PEPP as a ‘non-standard monetary policy measure’ to deal with the risks to monetary transmission posed by the pandemic. It is in fact the eighth eurosystem bond buying programme. Three of these have been discontinued but there are four presently running:

1. Corporate Sector purchase programme (CSP)

2. Public sector purchase programme (PSPP)

3. Asset backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP)

4. Third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3)

Put simply, the PEPP can buy any bonds which these four programmes could buy, but crucially without any of the restrictions applying to the programmes. By way of example, the PSPP – by far the largest of the four with €2.3 trillion outstanding as of December 2020 – cannot purchase more than 33% of either any individual issue, or the total bond debt, of a member state or its state agencies. The limit is 50% for supranationals. Given that the PEPP is presently sized at €1.85 trillion, it is therefore possible both for the PSPP to offload securities into the PEPP to allow further PSPP headroom, and for the PEPP to purchase 100% of new public debt instruments and then sell into the PSPP up to its respective maximum volumes.

The significance of the limits cited above, together with other restrictions such as the prohibition against asset purchases in the primary market (i.e. direct purchase of new bond issues at inception), and the obligation to purchase in accordance with the pro-rata ownership interest of each member state as determined by their ECB capital key, cannot be overstated. It was the presence of these rules, together with confirmatory reports from the ECB demanded by the German Constitutional Court, which persuaded the Court to conclude in May 2020 that these four asset purchase programmes were not ultra vires i.e. beyond the powers mandated to the ECB. Had the court ruled differently, the Bundesbank would have been prevented from participating fully in these programmes.

As mentioned above, other than a mild reference to ECB capital keys serving as a guideline, none of the asset purchase programme restrictions apply to the PEPP. In fact, it is highly likely that the May 2020 German court ruling was especially useful to the ECB lawyers when drafting the detailed PEPP provisions; they appear to have considered every specific limitation of ECB power which comforted the court, and then overridden every single one of them.

PEPP in the Context of TLTRO and Next Generation EU

In order to grasp the scale and impact of the present level of central bank money creation, it is important to consider PEPP in the context of two other sizeable liquidity activities.

a) Targeted Long Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO)

Although originally introduced in 2014 to directly finance banks, TLTRO has been consistently rolled over and increased in size. Commercial banks are required only to send a schedule stating ‘outstanding reference amounts’ of loans to their national central bank which is then authorised to finance up to 55% of ‘eligible’ loans. No actual pledge or hypothecation takes place, and the eligibility test is generous. The borrowing rate varies on a sliding scale peaking at minus 0.5%, thus rewarding banks who borrow the most by paying them ‘negative interest’. Data Published end March showed total TLTRO outstanding of €2.1 trillion. The impact of TLTRO has been to roll over previous ECB refinancing operations, and to replace interbank market funding, but not to increase loans as is publicly claimed by the ECB.

b) Next Generation EU Fund

In July 2020, even though the authorised PEPP limit was then €1.3 trillion, in response to powerful demands from weaker members states for grants rather than loans, a €750 billion fund through the EU and not the ECB was announced. Comprised of €390 billion of grants and €360 billion of loans, this facility will be administered by the Commission and is incorporated into the EU’s 7 year budget 2021 – 27. The grant component has crossed what was previously regarded as a Rubicon, namely that members states should not directly subsidise one another.

Most member states have now ratified this Coronavirus Recovery Fund, labelled NextGen EU. There was a ripple late in March when the German Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe blocked Germany’s potential ratification, but less than a month later the same court unblocked ratification, on the grounds that the consequences for Germany would be worse if NextGen EU were subsequently found to be constitutional. This decision is likely to encourage the remaining few member states who had not already ratified, so to do.

Although it is understandable that politicians such as Antonio Costa of Portugal incline to trendy language, hailing NextGen EU as kickstarting a “green and digital recovery” [[Twitter, March 26]], the early signs are that this fund is openly being used as a political tool to reinforce the authority of the Commission. For example, Ireland’s highly advantageous corporation tax regime now looks under threat from the Commission , which might prevent Ireland from accessing the NextGen funds unless Dublin accepts to “harmonise” its tax regime.

Conclusion – Financial Market Shrinkage

Whilst mainstream media, particularly in the UK, have quickly grasped the political impact and the arrogation of further powers by the Commission of the NextGen EU fund, the pithy technical nature of PEPP and of TLTRO have largely escaped mainstream critical analysis. This is an oversight. A recent OMFIF paper[[OMFIF is the “Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum”, and independent institute based in London]] points out that PEPP, together with the four asset purchase programmes, bought 95.5% of all 2020 new public debt instruments issued by euro area member states. The paper concludes that the ECB is breaking EU Treaty law, a point that will be tested in the German court eventually.

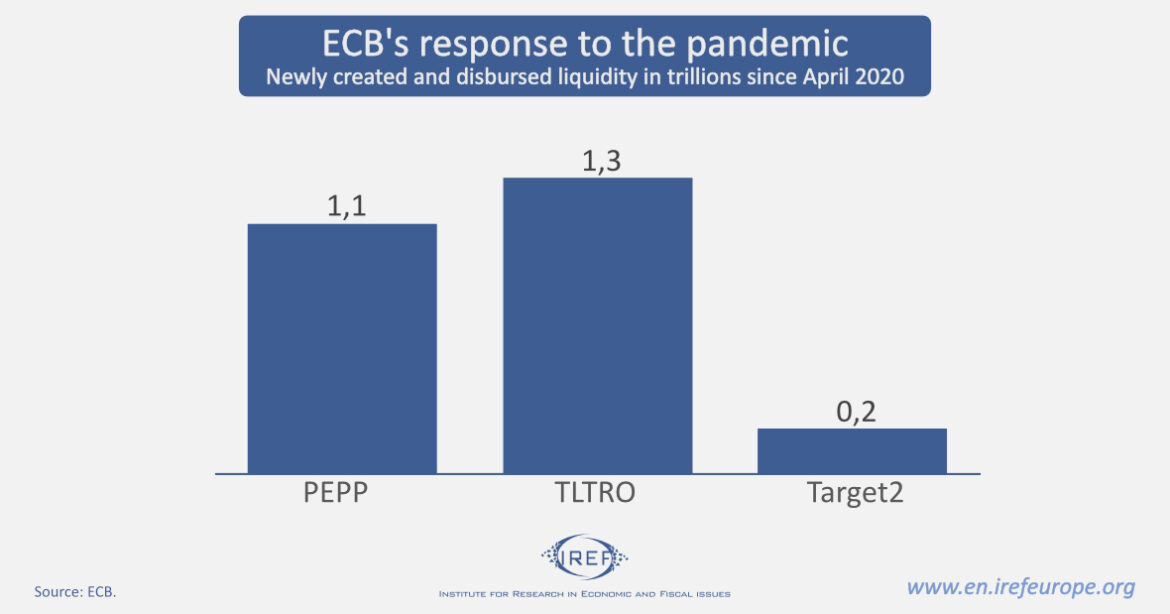

However, your authors’ view is that legal compliance is a trivial point compared to the shrinking of markets. It is no exaggeration to conclude that the ECB has more or less replaced financial markets with its printing press: PEPP plus the ongoing programmes for public debt, and TLTRO for banks. The previously reported Target 2 balances have also increased by some €225 billion in the past year. We summarise the volumes of newly created and disbursed liquidity under each of the programmes since April 2020: [[PEPP balance at date of writing: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2020/html/ecb.fst200331.en.html .TLTRO balance of €2.1trn on Eurosystem weekly financial statements as at 26 March 2021: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2021/html/ecb.fst210330.en.html . Compared to €825bn on 27 March 2020: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/wfs/2020/html/ecb.fst200331.en.html . Credit balances in TARGET2 as at end March 2021 compared to end Q1 2020, were €1.6 trn vs €1.4 trn: https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/reports.do?node=1000004859]]

The total of €2.6 trillion of new liquidity is equivalent to about 25% of euro area GDP. The NextGen EU fund has yet to start disbursing. There is no way back, no reverse gear. EU federalists may be presently happy that the direction of travel appears to be towards the creation of a European superstate, but we would caution that this vision remains way off in the distance, and the present focus should be on the dangers to Europe’s economy of money printing on this scale and its masking of problems in banks.