According to a recent survey across 34 countries, more people worry about income inequality than about the current COVID-19 pandemic. Pessimism with regard to inequality appears to be particularly widespread in France, followed by Spain, Greece, and Germany.

Global inequality increased until the 1970s/80s. Yet, more recent historical developments show a different picture. In fact, global income inequality decreased significantly during the past decades. Those who care about decreasing global inequalities should advocate better institutional contexts, to enhance growth in poorer countries and ease migration flows on a global scale.

Inequality is hard to measure

Capturing financial inequality is not easy. The primary question is whether it is about wealth or income. Moreover, it is not always easy to collect good-quality data. In order to compare income internationally, various methods for data collection can be used – for example household surveys, GDP per capita, or national consumption statistics. Although the findings differ depending on the chosen method, some general trends stand out.

Three stages of inequality

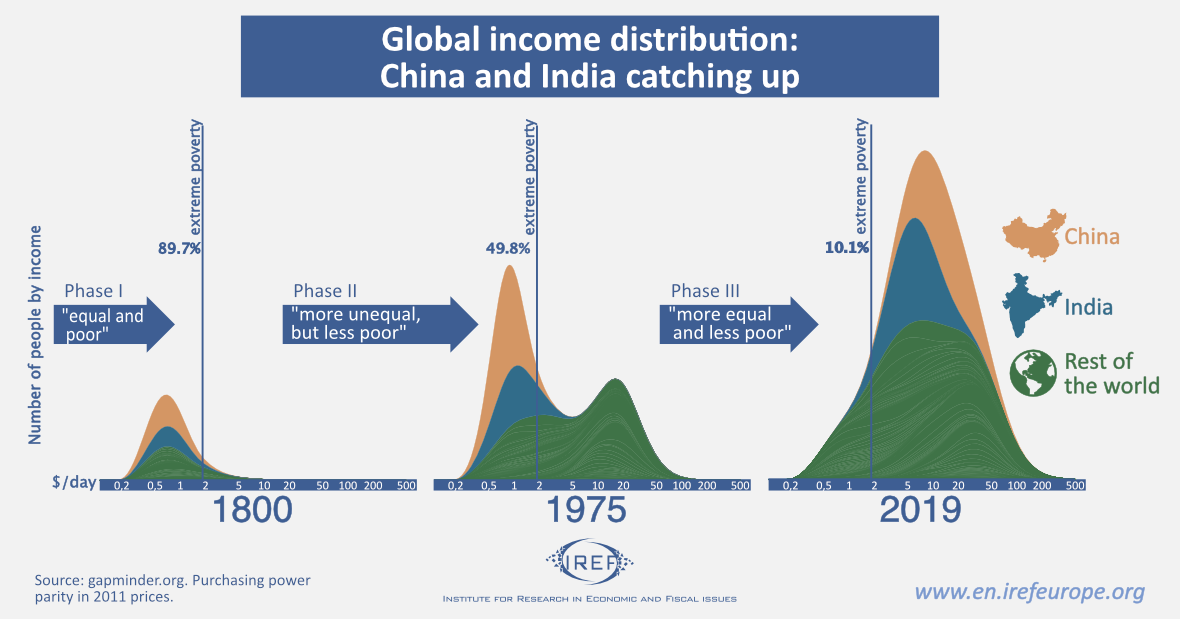

The historical development of global inequality can be roughly split into three phases. Until the beginning of the industrial revolution, the vast majority of people lived in extreme poverty, i.e. with less than the equivalent of $1.9 a day. In 1800, almost nine out of ten people lived in extreme poverty. Global distribution of income was relatively equal. The phase until the first industrial revolution can be summarised as “equal and extremely poor”.

About 175 years later, the picture had changed significantly. Compared to 1800, the 1975 situation could be characterised as “less equal, but also less poor”. Global inequality had increased significantly, and the distribution had a double-hump, almost camel-like shape. Indeed, a lot of people continued to live below the poverty line. However, as opposed to the pre-industrial age, one of those “humps” lied above the poverty threshold, and the percentage of people in extreme poverty had decreased to one half of the world’s population.

By contrast, the 2019 data shows a distribution that can be described as “more equal and less poor” compared with previous time periods. The camel is history: Global income distribution no longer features a “rich West” and a “poor rest”. Instead, it presents a global middle class that is clearly located beyond the poverty threshold. In particular, economic growth in Asia – China and India above all — has led to a more equal distribution. Only one out of ten people lives in extreme poverty, and inequality is significantly less pronounced.

Inequality has declines since the 1970s/80s

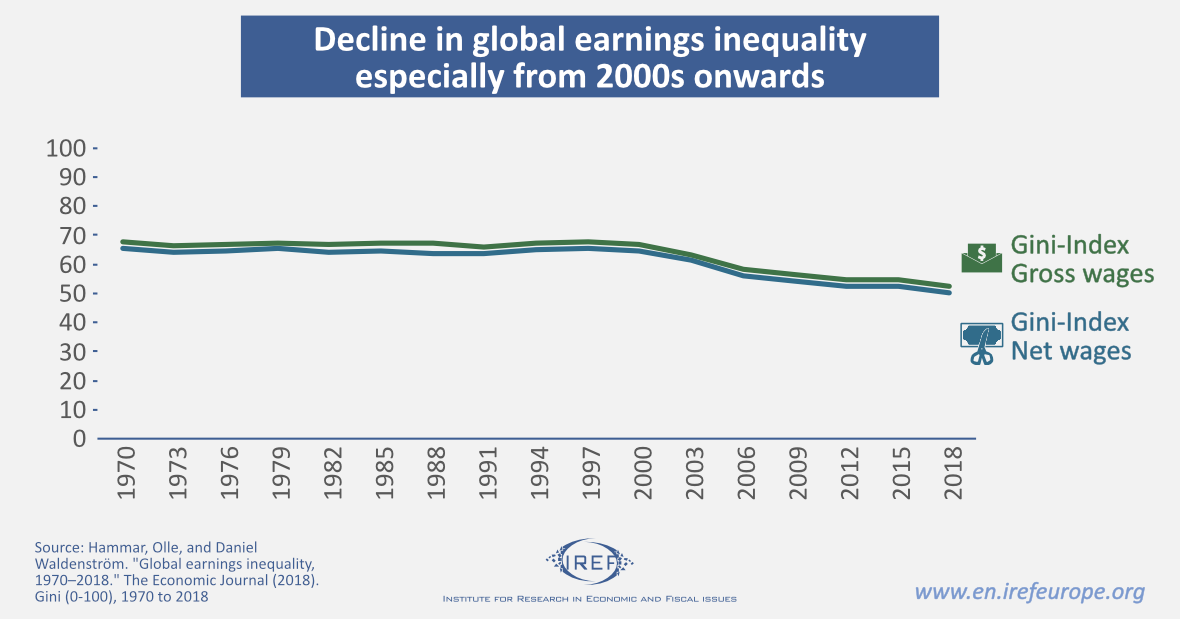

Research by Hammar and Waldenström (2018) confirms that global inequality has declined in the past decades. They utilised detailed earnings data instead of average incomes of individual countries. This accounts not only for inequalities across countries, but also within countries. Their data, however, ignore capital income. Consequently, the analysis underestimates actual inequality, but it finds trends similar to those from studies that do take capital income into consideration.

Hammar and Waldenström use the Gini index for measuring inequality; low values indicate a decline in inequality. According to their results, the global Gini index decreased by about 15 points – from 65 to 50 – during the past 20 years.

Growth and international trade

Moreover, Hammar and Waldenström find evidence that income convergence was predominantly driven by wage increases in sectors with traditionally tradeable goods, as opposed to the service sector. This can be interpreted as a telltale sign for the role of global trade in regard to global inequality.

Migration against global inequality

Like Hammar and Waldenström, economist and inequality specialist Branko Milanović relates a large share of the decline in global inequality to economic growth in Asia.

For the 1990s-2000s, he observes a relatively high income growth for all income groups, except for the lower middle classes in industrialised countries.

As Milanović emphasises, migration can contribute to a further decrease in global inequality. People in rich countries profit from a “place premium”: income is to a significant extent determined by the country people live in. If people migrate from a relatively poor country to a relatively rich country, their income increases significantly. This applies to German people moving to Switzerland just as much as to Vietnamese people moving to Germany.

In order to increase the domestic population’s acceptance of migrants in relatively rich countries, Milanović suggests that the rights of migrants compared with citizens be limited. For example, migrants could be treated differently with regard to taxation, or their stay could have a time limit.

Good development is not coincidental

Contrary to public perception, global income inequality has decreased significantly in recent years. This is not a coincidence: including poorer countries in the global division of labour has been effective has paid off. Economic growth in poor countries has contributed significantly to the reduction of global inequality, and many people have managed to break out of extreme poverty. Lower barriers to immigration could lead to migration playing a bigger role in future reductions of extreme poverty and global inequality.